- Home

- Vicki Delany

Silent Night, Deadly Night Page 5

Silent Night, Deadly Night Read online

Page 5

The women were seated in comfortable chairs, and two bottles of wine—one red and one white—were on the coffee table next to platters of cheese, crackers, and a thinly sliced baguette. Heads turned as I came in, and glasses were raised in greeting. Mom leapt to her feet and gave me a hug. “Thanks for coming, dear,” she whispered into my ear. She’d tried to tone her clothes down a bit tonight, I thought. She wore a plain black dress with a wide black belt under a red jacket, and her only jewelry was red glass earrings that caught the candlelight when she moved. I smiled to myself. My mom couldn’t be toned down even when she tried.

“My pleasure,” I said, returning the hug.

Mattie ran past me into the room, eager to meet the women. I’ve always maintained you can tell a lot about a person’s character by the way they react to animals. Constance smiled; Genevieve sniffed in disapproval; Karla recoiled and said, “Keep him away from the food”; Ruth gave him a brief pat; and Barbara immediately dropped out of her chair to roll on the floor with him. Vicky, seated in the leather wingback chair next to the fireplace that was usually my dad’s chair, grinned.

“My goodness,” Genevieve said. “Is that a dog?”

Or a pony, I finished silently.

“Or a pony?” she asked.

“This is Matterhorn,” Mom said. “We call him Mattie.”

“My aunt breeds kennel-show Saint Bernards,” Vicky said. “But poor Mattie here was born on the wrong side of the blanket, so Merry took him in.”

Constance laughed, and Karla threw her a look.

Vicky snapped her fingers, and Mattie went to her instantly. She gave him an enthusiastic rub around his neck and then said, “Sit,” and pointed to the floor next to her chair. He gave her an adoring look and then he politely sat.

“Can I get you a glass of wine, dear?” Mom asked me.

“I can help myself, thanks.”

I did so and then settled into an armchair on the other side of the fire from Vicky. Mattie curled up on the floor between us. “Did you all have a nice day?” I asked. I looked around the room, checking each of them out. I doubted any of these women would be brazen enough to wear an item they’d stolen from me in front of me, but you never know; they might not have realized I’d be coming to dinner.

I didn’t see a Crystal Wong necklace.

Constance looked very ladies-who-lunch-after-tennis in a Ralph Lauren navy blazer over a blue and white striped T-shirt and white slacks. Small gold hoops were in her ears, a diamond necklace was around her throat, and a thick gold band circled her left wrist. Ruth wore jeans, a V-necked T-shirt, and no jewelry except for her small wedding band and engagement ring. Barbara was in a brown turtleneck sweater and multi-pocketed khaki pants and sneakers. Karla’s brown dress was plain and didn’t fit her very well. Either she’d put on weight since she’d bought it or it had shrunk in the wash. For a touch of color, she’d wrapped a blue cotton scarf tightly around her neck. Genevieve wore a silver sheath dress that showed every sharp angle and protruding bone in her lean body, with large silver earrings and a matching necklace. The scent of tobacco hung over her like an aura: she must have been smoking only moments before we arrived.

“A very nice day,” Barbara said in answer to my question. “I went for a long hike this morning in the woods outside of town. There’s nothing like the woods of Upstate New York for getting back to nature. You lot should have come. Although”—she glanced at Karla—“some of you might not have been able to manage. It looks like it’s completely flat around here, but that can be deceiving. It turned into quite an energetic hike. Even got my heart rate up.”

“Is that all it takes these days,” Genevieve said, “to get your heart rate up, Barbara?”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“I seem to remember you were one for the boys, back in the day.”

“What of it? I was young once. So were you, but I’ve realized it’s time to stop pretending I still am.”

Genevieve bristled. I was pretty sure she’d had some plastic surgery: her face barely moved. “You were particularly fond, Barbara, as I recall, of the younger ones. One advantage of getting old: these days they’re all younger than us.”

Constance wiggled her eyebrows in delight at my mom, and Mom pretended not to notice. Vicky caught my eye and made a small round O with her lips.

“We don’t need to rehash old stories,” Ruth said.

“Why not?” Karla said. “Isn’t that why we’re here? We don’t exactly have anything in common anymore. Not that we ever did. Whatever happened to David anyway, Barbara? Are you still married to him?”

“As you well know, Karla, that ended a long time ago. David and I divorced amicably, and I’m now happy with Benjamin.”

“And how old might Benjamin be?” Karla asked.

“Whoa there,” Ruth said. “That’s totally uncalled for.”

“Don’t worry about it, Ruth. I say, good for Barbara.” Genevieve leaned back and crossed her legs. She sipped at her wine. “Some of us, at least, can still attract a handsome man. I saw the pictures of your children and grandchildren you were passing around, Karla. An attractive family. I assume they take after their father?”

Constance smirked and leaned over to grab the wine bottle. She poured herself a generous amount. Karla looked confused. She wasn’t entirely sure whether or not she’d been insulted.

“Karla married her childhood sweetheart,” Mom said to Vicky and me. “Not long after college. I had to wait a few more years until I found the right man.”

“You should be glad of that,” Constance said. “Otherwise it might be you keeping the books, of all boring things, for a minor construction firm in the boonies of the Midwest instead of being a hugely successful opera star.”

My mom had spent her career in the cutthroat environment of world-class opera. She had been a diva, and she sometimes acted like one, but she knew when not to take jealous digs personally and when to let minor rivalries go. Because she’d worked mostly in New York City, where she kept an apartment, and traveled extensively, Eve, Chris, Carole, and I had been raised more by our father than our mother. Dad was a practical, down-to-earth, small-town Upstate New York man—and proud of it. My parents were totally mismatched in almost every way, but not for a minute did I or anyone else doubt their devotion to each other.

“At least I do an honest day’s work for a living,” Karla snapped. “My husband and I built our company up from nothing. Together we created a business and a loving, thoughtful, close family. I never asked to have everything handed to me on a silver platter.”

“I assume you’re referring to me, and I’ll have you know I’ve worked hard for what I have,” Constance said.

“You mean you used your daddy’s money to work hard for you,” Ruth said. “Must be nice.” She cut off a thick slice of creamy gorgonzola and spread it on a cracker.

Constance’s eyes narrowed. “Careful, Ruth, you’re turning green. Even greener than usual, I should say.”

Genevieve laughed. Ruth popped the cheese into her mouth and chewed with angry bites.

My mom threw me a pleading look. I passed the look on to Vicky. None of us knew what to say to stop what was rapidly turning into a multi-way argument.

“Did I forget to offer you my condolences on the untimely death of your husband, Constance?” Karla said. “Didn’t the newspapers say something about suspicious circumstances?”

At last someone had gone too far.

The women gasped. My mother said, “I don’t think that’s at all appropriate, Karla.”

A vein pulsed in Constance’s temple. She gripped her wineglass so hard I feared it would shatter. “How dare you. At least I didn’t bore my husband to death with my endless complaining.”

“Isn’t this pleasant?” Vicky said. “When’s dinner? I’m starving.”

I wondered if t

hese women had always hated one another and they’d forgotten that as the years passed.

I glanced at my mother. Her color was high and she shifted uncomfortably in her chair. “Let’s not rehash old grievances,” she said. “We’ve been friends for a long time, and we’ve all lived good lives since.” She lifted her wineglass. “Let’s have a toast to the next forty years.”

“Easy for you to say, Aline,” Genevieve said. “You did okay in your career before you quit to bury yourself in this backwater of a town.”

“Hey!” I said. That dig was as sharp and vicious as Genevieve’s long red nails.

Mom lifted her left hand. The diamond on her finger flashed. “I took advantage of an opportune time to retire from performing, yes. I’ll admit that I had some luck in my career, also in my choice of life partner and in our children.” She smiled at me. “But far from being retired, I teach singing, trying to pass on some of what I learned to another generation.”

“Your luck,” Genevieve said, “as you call it, was having a voice suitable for an art form that doesn’t care how, pardon me, hefty or old a female performer might be.”

Mom sucked in a breath. My mother wasn’t fashionably thin, that’s true, but she didn’t fit the cartoon image of an opera diva, either.

Vicky put her wineglass on the table with a loud thud. “That’s mighty rude. What’s the matter with you people? Aline’s invited you into her home for a nice weekend and a chance to get to know each other again, and all you can do is snipe at each other.”

“I haven’t been sniping,” Karla said.

“You haven’t stopped,” Vicky said. “I’m going home.” She stood up. Mattie leapt to his feet. “Thanks for the invitation, Aline, but it’s late and I have to work tomorrow.”

“Please don’t hurry off,” Mom said. “Dinner should be ready by now.”

I gave Vicky what I hoped was an unobtrusive signal. If I had to suffer through this, the least she could do would be to keep me company. She grimaced but made no further move toward the door.

“Vicky’s right,” Ruth said. “Let’s forget our grievances and have a nice, pleasant evening.”

“Easier for some to forget than others,” Karla said.

“What does that mean?” Ruth asked.

“For some of us, the past isn’t past and we can never forget things that have happened.”

“Be that as it may,” Mom said, rising to her feet. “I can foretell the future, and I see dinner. Come along, everyone.”

The women stood and picked up their glasses. Constance snatched the bottle of white wine and carried it to the table, and Karla brought the cheese plate. Mattie hurried to be first into the dining room.

Mom and I stood back, and Vicky joined us. “Your friends aren’t nice,” Vicky said softly.

Mom shrugged. “I must have forgotten that.” The smile she gave me was tinged with sadness. “Perhaps I didn’t forget entirely, which is why I invited you to help smooth the waters. I’m glad you brought Vicky. Please stay for dinner, dear.”

“Good food, plenty of wine, conversation as sharp as you’d find in a Broadway play. What’s not to like?” Vicky said.

“You have a seat, Mom,” I said, “Vicky and I will serve the food.”

Mattie knew better than to beg for scraps at the table, but he made sure to curl unobtrusively underneath, just in case something tasty dropped to the floor.

Vicky and I went into the kitchen. She took oven mitts down from the hook and opened the oven door. We were enveloped in a wave of heat, and she pulled out a meat pie, fragrant and steaming, juices bubbling. “Did you make that?” I asked. “Smells wonderful.”

“No, I didn’t. We were so busy today, I had nothing left over. I brought the bread and the cheese tray we had for appetizers. And some mince tarts for dessert.” She next took a covered casserole dish out of the oven. “I assume we’re having this, too.”

I peeked into the white bakery boxes. One held eight of Vicky’s mince tarts and the other a big round chocolate cake. I opened the bag of salad ingredients that would be my contribution to the feast, dumped them into a bowl I found in the cupboard, and tossed all the ingredients together with packaged dressing, under Vicky’s disapproving eye. Before I bought it, I’d read the ingredients list on the bottle of dressing carefully to ensure it didn’t contain peanuts. Salad made, I helped Vicky carry bowls and casserole dishes into the dining room, and we piled the table high. As well as the meat pie, fragrant with steam, there were several salads, a couple of hot casseroles, and rolls and butter.

That done, I found a seat between Barbara and Ruth. Karla was on the opposite side of me, between Genevieve and Constance. Mom sat at the head of the table, and Vicky took the foot.

The candles on the table had been lit and the overhead light dimmed. The crystal and silverware sparkled, and the women were smiling.

“Everything looks marvelous,” I said. “And smells even better. What did everyone make?”

“Cooking in someone else’s kitchen’s always a challenge,” Ruth said. “But I enjoyed it. The duchess potatoes are mine.”

“Quinoa and black beans from me,” Barbara said. “That’s my specialty. It’s best served at room temperature. I often make it on backcountry hiking trips because the ingredients are dry and easy to carry.”

“I’m sure it tastes like it, too,” Karla said.

“You are welcome not to have any,” Barbara said.

It was a good thing my father wasn’t here this weekend. He would have thrown more than one of these women out of the house long before now.

We began passing bowls and platters around.

“I made the kale salad,” Genevieve said. “It would have been a lot better with arugula, but we were too late to the market to get any, so I had to compromise.”

“The chicken casserole is mine,” Mom said. The bowl was passed to me, and I gave myself a generous helping, thinking maybe this dinner wouldn’t turn out to be so bad after all. I love my mom’s chicken casserole, made with mushrooms and tomatoes and a generous slug of good red wine.

“I made the steak-and-mushroom pie,” Karla said. “It’s always been my husband’s favorite, and we have it a lot at home. If there’s one thing I’ve learned over the years, it’s the importance of keeping your man happy through his stomach.”

If that was intended to be a dig at the salad-making women, Vicky destroyed the moment by laughing. “My boyfriend’s a chef. He makes himself very happy through his stomach.”

“I’ll confess that I used premade pastry,” Karla said. “It’s not quite the same, is it?”

“It smells fabulous.” Vicky cut herself a big wedge.

“I’m not much of a cook,” Constance said. “So I cheated and went to Vicky’s bakery and got a cake for dessert.”

When we’d all been served, Mom tapped her fork against her glass. “A toast,” she said.

The women lifted their glasses.

“To old friends,” Mom said. “Like all people, we occasionally have our differences, but our memories of our past binds us in friendship.”

“Hear! Hear!” Ruth said.

“To old friends,” the others chorused.

“I prefer to say ‘friends of long acquaintance,’” Barbara said, and several of the women laughed.

Formalities over, we dove into the meal. Even Genevieve served herself healthy portions, although her plate was heavy on the salads.

“Your mother tells me you aren’t married yet, Merry,” Karla asked. “Any prospects on that front?”

That was a startlingly personal question. I glanced up in time to see Vicky stuffing a bread roll into her mouth in an attempt not to break out laughing. “Maybe. Maybe not,” I said. “Early days yet.”

“You’re still young,” Karla said. “Plenty of time left.”

I didn�

�t bother to reply that I wasn’t all that young and time was rapidly passing. I helped myself to a generous serving of curried egg salad.

“Although, I must say, grandchildren are life’s greatest pleasure.” Karla looked around the table, almost, I thought, daring some of the other women to disagree. “Far more than any successful career.”

But the good food must have been making them all mellow, and no one rose to the bait. Genevieve mentioned that she’d had an audition for a new Netflix production and she was confident of getting the role. Mom wished her well.

Ruth asked Vicky what it was like to own a busy bakery, and Constance told me she and her son were going to Paris for the holidays this year. She began telling us how beautiful Paris was at Christmas.

“Must be nice,” Karla muttered under her breath.

“Does your family spend Christmas with you?” I asked her. The bowl of curried egg salad sat in the middle of the table, between me and Karla. It was absolutely delicious. I reminded myself there were mince tarts and chocolate cake for dessert, but then helped myself to another serving of the eggs anyway. I passed Karla the spoon, and she also took another helping.

“They’re so busy with their own lives,” she said. “That’s life these days, isn’t it? My son’s working up until Christmas Eve, and he doesn’t want to have to drive to our place at night, particularly if it snows, not with those precious children in the car. My daughter will be spending the holidays with her in-laws this year.” She ate rapidly, with short angry bites, barely taking time to swallow. “I’ll miss the grandchildren, but there’s something to be said for a peaceful, relaxing Christmas once in a while, isn’t there? Eric and I will enjoy a nice quiet celebration on our own this year.”

Her eyes slid to one side and she patted her hair. She was lying, more to herself, I thought, than to us. A quiet Christmas could be very nice indeed, but only if that’s what you wanted. “Children these days can’t find a minute to visit their parents.” She looked at the woman seated next to her. “You’re lucky, Constance, that your son’s willing to give up his own plans to spend the holidays with you.”

Silent Night, Deadly Night

Silent Night, Deadly Night Coral Reef Views

Coral Reef Views Deadly Summer Nights

Deadly Summer Nights Murder in a Teacup

Murder in a Teacup Whiteout

Whiteout Dying in a Winter Wonderland

Dying in a Winter Wonderland Tea & Treachery

Tea & Treachery Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen

Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery Body on Baker Street

Body on Baker Street Gold Mountain

Gold Mountain Blue Water Hues

Blue Water Hues Hark the Herald Angels Slay

Hark the Herald Angels Slay Murder at Lost Dog Lake

Murder at Lost Dog Lake Blood and Belonging

Blood and Belonging A Winter Kill

A Winter Kill White Sand Blues

White Sand Blues Scare the Light Away

Scare the Light Away Burden of Memory

Burden of Memory More Than Sorrow

More Than Sorrow In the Shadow of the Glacier

In the Shadow of the Glacier Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery

Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery Gold Web

Gold Web Haitian Graves

Haitian Graves Valley of the Lost

Valley of the Lost We Wish You a Murderous Christmas

We Wish You a Murderous Christmas Negative Image

Negative Image A Scandal in Scarlet

A Scandal in Scarlet Juba Good

Juba Good Winter of Secrets

Winter of Secrets Unreasonable Doubt

Unreasonable Doubt Gold Fever

Gold Fever Among the Departed

Among the Departed Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

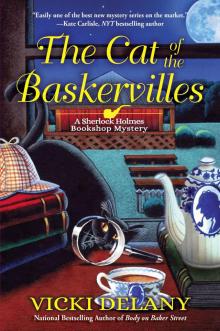

Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery The Cat of the Baskervilles

The Cat of the Baskervilles