- Home

- Vicki Delany

Juba Good

Juba Good Read online

JUBA

GOOD

VICKI DELANY

Copyright © 2014 Vicki Delany

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Delany, Vicki, 1951-, author

Juba good / Vicki Delany.

(Rapid reads)

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4598-0490-6 (pbk.).--ISBN 978-1-4598-0491-3 (pdf ).-

ISBN 978-1-4598-0492-0 (epub)

I. Title. II. Series: Rapid reads

PS8557.E4239J82 2014 C813’.6 C2013-907626-3

C2013-907627-1

First published in the United States, 2014

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013956420

Summary: RCMP Sergeant Ray Robertson, nearing the end of his year-long UN mission in Juba, South Sudan, struggles to find a serial killer. (RL 3.0)

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for its publishing programs provided by the following agencies: the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Design by Jenn Playford

Cover photography by plainpicture

In Canada:

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 5626, Station B

Victoria, BC Canada

V8R 6S4

In the United States:

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 468

Custer, WA USA

98240-0468

www.orcabook.com

17 16 15 14 • 4 3 2 1

For Caroline

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter One

I jumped out of the way of a speeding boda boda and tripped over a pregnant goat. The driver of the scooter yelled at me. I gave him a hand gesture in return. Not a good idea, in this town, at this time of night. But I’d had a rotten day and was in a matching mood.

The goat I ignored. It was not a good idea to interfere with her. She was worth money.

Juba, South Sudan. April. The dry season. The air red with dust blowing down from the desert to the north. Choking dust. Getting into everything. Me, coughing up my lungs half the night.

At six foot three, I’m considered a big guy back home in Canada. Here, in a group of locals, I’m about average. Some of these guys—heck, some of the women—must be close to seven feet. Damn good-looking women though.

My name’s Ray Robertson. In Canada, I’m an RCMP officer. In South Sudan, I’m with the UN. Our role is to be trainers, mentors and advisers. Help the new country of South Sudan build a modern police force.

Yeah, right.

I’ve been in the country eleven and a half months. Just over two weeks to go. First thing I’m going to do when I check into my hotel in Nairobi is have a bath. A long hot bath. Get all that red dirt out of my lily-white skin. Jenny gets in the next morning. We’re going to Mombasa. A fancy hotel. A week on the beach. Sex and warm water and clean sand. More sex. Heaven.

I climbed into the police truck. I’d recently begun working with John Deng. He was a good guy, Deng. From the Dinka tribe, so about as tall and thin as a lamppost. He didn’t say much, but what he did say was worth listening to.

His phone rang. Deng spoke into it, a couple of short words I didn’t catch. He hung up and turned to me. His eyes and teeth were very white in the dark.

“Another dead woman,” he said.

“Damn.”

Deng put the truck into gear and we pulled into the traffic. Think you’ve seen traffic chaos? Come to Juba. The city’s mostly dirt roads. Uncovered manholes, open drainage ditches and piles of rubble. Potholes you could lose a family in. Trucks, 4x4s, cars, boda bodas, pedestrians, goats, chickens and the occasional small child. Every one of them fighting for space, jostling to push another inch through the crowds. The roads have no street signs and few traffic signs. Which no one pays attention to anyway.

We drove toward the river. The White Nile. The goal of Burton, Speke, Baker, the great Victorian explorers. The river’s wide here, moving fast. It’s not white for sure. More the color of warm American beer. Full of twigs and branches and whole trees trapped in the current. Plus a lot of other things that I don’t want to think much about.

The old settlement’s called Juba Town. Disintegrating white buildings, cracked and broken sidewalks, mountains of rubbish. A crumbling blue mosque in a dusty square. Small shops selling anything and everything alongside outdoor markets hawking goods.

In daytime, the streets are crowded. Soldiers in green camouflage uniforms. Police in blue camo. Adults going about their business. Bare-bottomed babies. Schoolchildren with scrubbed faces, clean uniforms and wide, friendly smiles. Honking horns, shouting men, chatting women, music and laughter.

Now, at night, all was quiet. A handful of fires burned in trash piles that had spilled into the streets. Men sat in circles drinking beer. Women watched from open doorways. Above, thick clouds blocked moon and stars.

A water station had been built close to the river. Blue water trucks lined up there during the day to get safe water. The street was a mess of deep puddles, red mud, rocks, ruts and trash. Not as good as some, better than most.

Deng stopped our truck at the bend. Where the road turned sharply to run parallel to the river. He left the vehicle lights on and we got out. I pulled my flashlight out of my belt. Flashlight and a night stick. That’s all I carried. No weapon. This was a training mission, remember. I was here to observe. To offer comments and helpful ideas when needed.

A year without the Glock, and I still felt like I had a giant hole in my side.

Deng carried an AK-47. He was former army, SPLA—Sudan People’s Liberation Army. At first a band of guerillas, fighting for independence from Sudan. Now the army of South Sudan. He’d spent his time in the bush during the war, doing things I couldn’t imagine. Things I didn’t want to imagine. The long and brutal civil war had made these people hard. Some of them didn’t handle it too well. Deng did. He had a quick smile and a hearty laugh. He wanted to be a good police officer. I’d asked him once if he had a wife and children. A mask settled over his face. He yelled at the driver of a scooter who hadn’t come at all close to us. I never asked again.

The woman was lying at the side of the road, up against a concrete wall. Her skin was as black as midnight. Blacker. An earring made of red glass hung from her right ear. A short tight black dress and red stilettos were clues to her occupation. Another dead hooker in the dusty red streets of Juba.

This was the fourth. If she was a hooker. If the same person had been responsible. The fourth in three weeks.

Deng snarled at the security guard who’d found her. The man quickly stepped back. He knew his place.

I used my Maglite to illuminate the scene. A white ribbon was wrapped around her neck. Wrapped very tightly around her neck. As white and pure as the snow on Kokanee Glacier in midwinter. Same as the others.

“What do you see?” I asked Deng. That’s the training part of my

job.

“A white ribbon.”

“Yup.”

“Do we have a serial killer here, Ray?”

“I’m beginning to think we do.”

Chapter Two

Forensic rules of evidence tend to be a bit wobbly in South Sudan. We wouldn’t be joined by a crew of techs in hairnets and white booties. No police tape. No fingertip search of the vicinity. No lab analysis. No DNA samples taken. No databases checked for similar cases. The body would be carted away and that would be the end of that.

Deng and I did what we could to examine the scene.

It looked as if she’d been taken by surprise. Strangled with the white ribbon. Left where she fell. No defensive wounds on her hands or arms. No signs of sexual activity.

Deng crouched down. “What does the ribbon mean?” He reached out one hand and ran his fingers over it very lightly.

“I don’t know. It means something to him. He might not even know what. Sometimes they leave a sign. Sometimes they take trophies.”

“Trophies?”

“Yeah. I don’t see anything missing here. Serial killers usually have a signature. His is the white ribbon.”

Deng shook his head. When you’ve seen so much death and dying, it’s hard to believe someone would do it for…fun?

At a guess—and it would never be more than a guess—she’d been dead about two hours. Not many bugs yet. No rigor mortis.

I’d once tried to explain rigor mortis to Deng and his colleagues. They’d nodded very politely. I’d felt like a total fool. These guys had seen more dead bodies than any undertaker in Vancouver. They knew the process of decay, thank you very much.

Sometimes they could be so goddamned polite. Why didn’t they just tell me to shut the hell up? Suggest we take the time allocated for the lecture to go for a beer?

Deng and I shone our flashlights around the area. I made notes in my notebook. And then we left. What else could we do? The carcass would be loaded into the back of a van and that would be the end of her.

The bend in the road was close to Notos. A good bar with a great Indian kitchen. I suggested we stop in for a drink. Deng looked surprised. We UN advisors told them drinking on the job was a bad thing. I winked and said it was all part of the job.

Which wasn’t a lie.

Notos was a popular spot. Aid workers and foreign government staffers hung out there. They might have seen something. The rest of the road was made up of tin shacks and cardboard houses. Plus a few of the traditional mud and grass huts called tukuls. No one there would help the police.

The fire in the pizza oven blazed. Spices filled the air. The bar hopped with good jazz.

The restaurant was full. I nodded to a couple of Canadian embassy staff. We went to the bar. I ordered two orange Fantas. Deng tried not to look too terribly disappointed.

The bartender was named Shirley. A knockout in a neat white shirt and black pants, with short-cropped black hair. She passed the bottles over with a soft smile. The smile was directed not at me but at Deng. He didn’t seem to notice.

“Busy tonight,” I said.

“Usual.”

“Some trouble out on the street earlier. A couple of hours ago. Maybe around nine. Did you hear anything, Shirley?”

She glanced at Deng from under her eyelashes.

He said, “Did you?”

“Can’t hear anything over the noise in here.”

“Did anyone go out for a break, maybe? Smoke. Get some air?”

A silent shake of her head. She slid down to the end of the bar to take an order.

That’s the problem with policing here. You don’t know what experiences people have had. In Canada, we get suspicious if someone avoids police questions. Most people want to be helpful. Whether they have anything to be helpful about or not. But here, with the trauma some of these people have experienced?

Maybe they’re as guilty as sin.

Maybe they don’t much care.

Maybe they’ve seen men in uniform slaughter whole families.

You just don’t know.

I visited the tables. I asked the same questions I’d asked Shirley. Got nothing but shakes of the head and questions back.

Only a shy young waitress named Marlene thought hard. I suspected Marlene liked me. I didn’t know if she really liked me or was just hoping for a visa to Canada. I made sure to always keep things light and no more than friendly. Tonight, she had nothing to say that would help us.

Back to the bar. I leaned against the counter and sucked on my Fanta. The restaurant was emptying out. People called good night to their friends in the warm night air.

A tall white woman, blond, pretty, came up to the bar. She dug in her purse. “I need more Internet time,” she said. “Can I buy three hours?” Her English was perfect, the Dutch accent strong. She gave me a smile as Shirley searched for the Internet vouchers. I hadn’t seen the Dutch woman when we came through the restaurant.

“Do you live nearby?” I asked.

“In the townhouses, yes.” Four modern townhouses were next to the restaurant. They were surrounded by a concrete wall. They boasted a rare patch of scrappy lawn and trimmed bushes.

“Were you outside earlier? Say around nine, ten?”

“Why do you ask?”

“Police business.”

Deng refrained from rolling his eyes. He thought I was trying to pick her up.

She laughed through a mouthful of perfect white teeth. “I had dinner with friends. Came home by taxi. Around nine, I think. What happened?”

“There was a killing. On the corner. Where the road bends.”

She lifted her hand to her mouth. “A killing? Who? Someone I know?”

“A local, probably.”

The concern faded from her face. “That’s very sad.”

“It might have been around that time. Did you see anything unusual?”

She hesitated.

“What?” I asked, my tone sharper than I’d intended.

Shirley passed her a slip of paper. “Twenty-five pounds.”

The Dutch woman handed over an orange bill. She chewed her lip. “I heard something.”

“Yes?”

“The air-conditioning wasn’t working in the taxi. The windows were down. I heard someone—a woman—scream.”

“And?”

“And nothing. Just a scream. Once only.” She looked away, embarrassed. “We drove on, and I heard no more. I’m sorry.” She scurried off.

I let out a long sigh.

“What did you expect, Ray?” Deng asked.

A good question. I expected nothing else, really. No one would want to get involved. Not many people would much care. What was the scream of a woman in the hot African night?

In Canada, plenty of people would have rolled up their windows too.

“Helps narrow the time,” I said, not very helpfully. “The state of the body indicated a time of death around nine. The scream was heard at that time.”

“Very helpful,” Deng said. I suspected he was being sarcastic.

I put the remains of my sickly sweet orange drink on the bar and stalked out. Deng followed, chuckling.

Chapter Three

Home sweet container.

I live in a shipping container in the UN compound. The walls are painted a practical beige. It has no art, no decorations, no rugs. In my good moods, I think of it as my man cave. The single bed’s moderately comfortable. The small desk has a flimsy office chair and a laptop.

It has plumbing and electricity. But it’s still a box.

Three pictures sit on the night table. Our eldest daughter at her wedding. Our second daughter at her university graduation. Jenny and me at our wedding. Looking so young, so happy. I had long curly hair back then. Not much of it’s left these days.

I didn’t sleep well that night. Not that it was night when I crawled into bed. The hot sun was rising in the eastern sky.

I’ve seen a lot in my time as a cop. More than I like to thin

k about sometimes. Not much bothers me anymore, unless it’s kids. I hate it when violence is done to kids.

But I couldn’t get the dead hooker out of my mind. She might not have even been a hooker. These days it’s hard to tell the hookers from the office workers out for a night on the town with their girlfriends.

The woman looked to be South Sudanese. These people had been through so much hardship. If the woman was in her twenties, chances were she’d never known anything but civil war.

Then to be killed, murdered, in a time of peace.

Life could be so damn unfair.

* * *

I rolled out of bed not long after noon. I pulled on white shorts and a Vancouver Canucks T-shirt and went in search of breakfast.

The UN compound is close to the center of Juba. It’s clean and tidy, with a bit of grass and some flowering bushes. Neatly swept footpaths and small houses with curtains in the windows.

Surrounded by concrete walls topped with razor wire.

Step out the gate and you’re in Africa.

I crossed the yard. The air was an orange haze. Everything was covered with dust. It hadn’t rained since October. Everyone was waiting, waiting, for the first rains of the season to fall and the heat to break.

The sun wasn’t visible through the murk. But I always wore a broad-brimmed beige hat to protect my balding head.

Two people were in the common room when I entered. Joyce, a tall lean Australian with a shock of wild red hair, was in uniform. She was eating eggs and reading. She lifted her head, said hi and returned to her food and book. Peter, a cop from Namibia, was sprawled across the badly sprung couch, watching TV. As always, a soccer game was on. I hate soccer. Give me a good hockey game any day. Even baseball’s better than soccer. But they sure love soccer in Africa.

I popped two slices of bread into the toaster. I twisted open the top of a jar of peanut butter. On the TV, the crowd roared. I didn’t bother to look up. No one would have scored. No one ever scores in soccer. They run around the field for two hours and then have a shoot-out to decide the winner. Might as well just have the shoot-out and everyone go home early. I grunted in disapproval.

Silent Night, Deadly Night

Silent Night, Deadly Night Coral Reef Views

Coral Reef Views Deadly Summer Nights

Deadly Summer Nights Murder in a Teacup

Murder in a Teacup Whiteout

Whiteout Dying in a Winter Wonderland

Dying in a Winter Wonderland Tea & Treachery

Tea & Treachery Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen

Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery Body on Baker Street

Body on Baker Street Gold Mountain

Gold Mountain Blue Water Hues

Blue Water Hues Hark the Herald Angels Slay

Hark the Herald Angels Slay Murder at Lost Dog Lake

Murder at Lost Dog Lake Blood and Belonging

Blood and Belonging A Winter Kill

A Winter Kill White Sand Blues

White Sand Blues Scare the Light Away

Scare the Light Away Burden of Memory

Burden of Memory More Than Sorrow

More Than Sorrow In the Shadow of the Glacier

In the Shadow of the Glacier Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery

Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery Gold Web

Gold Web Haitian Graves

Haitian Graves Valley of the Lost

Valley of the Lost We Wish You a Murderous Christmas

We Wish You a Murderous Christmas Negative Image

Negative Image A Scandal in Scarlet

A Scandal in Scarlet Juba Good

Juba Good Winter of Secrets

Winter of Secrets Unreasonable Doubt

Unreasonable Doubt Gold Fever

Gold Fever Among the Departed

Among the Departed Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

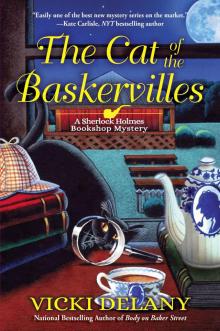

Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery The Cat of the Baskervilles

The Cat of the Baskervilles