- Home

- Vicki Delany

Unreasonable Doubt

Unreasonable Doubt Read online

Unreasonable Doubt

A Constable Molly Smith Mystery

Vicki Delany

www.VickiDelany.com

Poisoned Pen Press

Copyright

Copyright © 2016 by Vicki Delany

First E-book Edition 2016

ISBN: 9781464205163 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

www.poisonedpenpress.com

[email protected]

Contents

Unreasonable Doubt

Copyright

Contents

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Epilogue

More from this Author

Contact Us

Dedication

To Mom

Acknowledgments

I’d like to extend my sincere thanks to Bonnie Taylor and Pat Bradley and their team HEAT from the Quinte Dragon Boat Training Centre for taking me out on the water and introducing me to the fun of dragon boating.

Thanks to Cheryl Freedman and Melodie Campbell for reviewing and advising on the manuscript of this book. Some advice I took; some I didn’t. But all was carefully considered.

Thanks also to Barbara Peters for wanting another Smith and Winters, and for all her encouragement over the more than ten years I’ve been with Poisoned Pen Press, the world’s best publisher.

And to Nelson artist Maya Heringa for letting me put one of her beautiful paintings in the window of the Mountain in Winter Gallery.

For Merrill Young, who lent me the use of her name. Hope you like what I did with you, Merrill.

Epigraph

“We know not whether laws be right

Or whether laws be wrong

All we know who lie in gaol

Is that the walls are strong

And each day is like a year

A year whose days are long.”

—Oscar Wilde, “The Ballad Of Reading Gaol”

Chapter One

Walter Desmond felt something move, something low in his belly that he might once have recognized as happiness. It had been many years since he’d known what happiness felt like. He gazed out the window of the bus, full of wonder. The mountains were so high, the slopes closing in on the highway, their ragged tops still white with snow even though it was July. In the valleys, lakes and rivers sparkled blue in the sunlight.

A shade of blue he had forgotten could exist.

He’d forgotten the smell also. The rich scent of pine trees, leaf mulch, fresh water moving fast over rocks and boulders. Clean air, most of all.

This bus, however, smelled of nothing other than too many people crowded too close together, a scent Walt knew only too well. When they’d had a rest stop in Hope, and his fellow passengers streamed into Tim Horton’s, Walt had simply stood there, stunned, breathing it all in. Hope was the name of the town. Hope. He’d take it as an omen, because it had been a long time since hope had been more than a word with a meaning he’d forgotten. The mountains around Hope were almost vertical—a wall of dark green and brown. He might come back to Hope someday, but for now those mountains were altogether too close. He’d been hemmed in long enough. He closed his eyes and let his nose and ears explore the land around him until it was time to clamber back onto the bus.

As the bus travelled down the highway, and morning passed into afternoon, he could see that in all too many places the tall pines were a strange shade of brownish-purple, not the dark green he remembered. He’d read about the mountain pine beetle and the devastation the insects were bringing to this part of British Columbia as they killed every tree they encountered. He hadn’t realized how widespread the damage was. He hadn’t realized a lot of things. He’d read everything he could get his hands on and thought he’d be prepared when the day finally came.

He wasn’t. Nowhere near prepared. Everything was so strange. Like that TV show “Life on Mars,” in which the cop went back in time. Although in Walt’s case, he’d gone forward in time. To life on another planet.

The bus had WiFi. He knew what WiFi was. He’d read about it when he’d been allowed to use the library computers, where he’d tried to keep up with everything that was happening in the world without him. He’d heard about phones people carried in their pockets and were far more than just telephones, and about worldwide instant communication. He’d also heard about civilians using those phones to film cops smashing heads in. Or worse.

The woman in the seat beside him had a phone like that. It was white, but the case was brown with dirt. She spent a lot of time typing with her thumbs. He’d found typing difficult enough to get his head, not to mention his fingers, around. Back in the day, he’d had a secretary who did that typing stuff. But he’d worked hard at it; he’d been determined to learn. When he’d last been part of the working world, secretaries were being phased out. He understood that he’d have to type for himself. He had. And now was he was going to have to learn to do it with his thumbs or the tips of his fingers?

As a kid he’d loved those sci-fi TV shows and books where the astronaut, landing in some strange world that usually turned out to be Earth in the past or future, struggled to understand what was going on. It wasn’t fun, Walter Desmond knew, not fun at all in real life.

The woman put away her phone. She pulled a dog-eared paperback out of her bag. She was wearing too much perfume. As well as a lot of things, he’d forgotten the scent of cheap perfume. There had been nothing cheap about Louise. Not her clothes, her makeup, or her hair. And certainly not the perfume she wore—subtle, enticing. He felt himself smiling. It was a strange sensation. He ne

eded to get used to it.

He’d taken Louise’s hand as the lineup to get on the bus edged forward. A few people openly gaped at her. Not because they recognized her, but because she looked so out of place in the grimy bus station in her designer suit, ironed blouse, patent-leather high-heeled pumps, and tasteful gold and diamond jewelry.

“You’re sure this is what you want to do?” she said in her deep sexy voice.

“It’s what I have to do.”

“I might not approve, but I do understand.” She’d advised him not to leave Vancouver. Not yet. Get accustomed to the modern world first. But he knew he had to do it. Now. While he still had the nerve. He could feel the softness of her skin, the warmth of the blood beneath the surface, the delicate bones, the pressure of her ring. He took a deep breath, and slowly, reluctantly, released her. It was like letting go of a lifeline in a storm-tossed sea. From this point forward, he was on his own. “Thank you. For everything.”

Her eyes were warm. A smile touched the edges of her lips. “We won’t meet again, Walt.”

“I know.”

She turned and walked away, her heels clicking on the sticky floor. She pulled her iPhone out of her Michael Kors handbag and began pushing buttons. She was talking as she walked through the doors, paying no attention to the people who’d stepped back to allow her to exit. He smiled at the memory: the moment she turned her back on him, she’d been thinking about her next case. Another poor schmuck waiting for her to save him.

“Hey, buddy. Haven’t got all day here,” a man behind him had called. And Walt clambered onto the bus.

The woman beside him, the one with the heavy hand on the perfume bottle, took his private smile as an invitation. “On vacation?”

“What?”

“Have you been in Vancouver on vacation?”

“Oh. Vacation. No.”

“I’m going to Trafalgar to visit my daughter. And my grandchildren, of course. I have three now, two girls and a boy. There’s another on the way, although early days yet. Would you like to see a picture?” Without waiting for an answer she began rummaging through her cavernous purse to once again pull out her phone.

“No,” he said. He wished he could take back the word. He’d forgotten how to be polite. He shifted in his seat, stared out the window. The woman sniffed, but she took the hint and returned to her book.

What else had he forgotten? Pretty much everything that made life worth living. How to be polite, how to make money, how to drive a car, how to talk to women—other than Louise, and they’d certainly never engaged in small talk. He didn’t know how to use one of those small, sleek phones that fit into a pocket or how to find a WiFi connection. He couldn’t begin to understand the menu in the coffee shop, and when he asked for a coffee he didn’t understand what the girl meant when she asked if he wanted Pike’s Place.

His wife, Arlene, had passed away, shattered, defeated, brokenhearted, seventeen years ago. The day she died, he’d forgotten how to love.

But there was no forgetting how to hate.

Chapter Two

John Winters pulled up in front of a two-story heritage home close to the center of town. This was a nice street, the properties well maintained, the older houses either replaced by new ones of concrete, glass, and wood, or preserved in their historic glory.

The house he was interested in stood out from the others due to its state of considerable neglect. The front porch sagged at one end; the bottom step was broken. The fence and walkway were lined with what had once been lush perennial beds, but the hearty plants now struggled against an onslaught of weeds and invading grass. More weeds sprouted between the carefully laid bricks of the driveway.

“They’re only in their seventies,” Paul Keller said. “But not doing well at all. I believe the wife had a stroke a couple of years ago, and he has a bad heart.”

“They have any other children?”

“A son. Name of Anthony. He lives in Toronto, I think. Several years younger than Sophia. They pretty much stay under the radar. We’ve not had any contact with them since…since then, not until these new developments hit the papers. As hard as this is going to be, we have to do it. Might as well get it over with.”

The two men got out of the car.

A couple of kids came down the street on their bikes, enjoying the freedom of summer holidays. A sleek young woman in running gear passed, pushing a toddler in a jogging stroller. She nodded in greeting and went on her way, paying Winters and Keller no further attention. It was a hot day, and Winters felt the sun on his head and sweat under his arms.

A curtain twitched at a neighbor’s front window and he knew they couldn’t stand here all day. He let out a puff of air and walked up the cracked and weed-infested front walk beside the Chief Constable of Trafalgar. The porch steps creaked under their weight. An assortment of terra-cotta pots in various sizes lined the railing, overflowing with geraniums, begonias, and ivy. These plants, at least, were colorful and full of life.

Paul Keller knocked and the door opened.

The woman who stood there might have been in her nineties, but Winters knew she was only seventy-three. The years had been hard on her, indeed. She was very short at not much over five feet, wizened and frail. She leaned on a sturdy cane. Her face was heavily lined; her short, badly cut hair, steel gray; her brown eyes deep sockets in an olive face. “Chief Keller,” she said, “you have come to tell me the bastard’s dead. I’m glad of it.”

A man appeared at her side. He was her age, but he didn’t wear his grief and sorrow so prominently. “No, Rose,” he said. “That is not why they’re here.”

“May we come in?” Keller asked.

“Of course,” the man said. The woman, leaning heavily on her cane, turned without a word.

Winters and Keller followed them into the house. The carpets were threadbare in places, the paint on the walls in need of freshening, but otherwise things were neat and tidy. Winters recognized the symptoms: an old woman without the energy or dexterity to do a thorough cleaning anymore, but still house-proud; her husband losing interest in the minor handyman chores that had once kept him occupied.

He’d never been to this house before, had never met the D’Angelos. Yet he could sense the sorrow that hung over their house as if it were a dusty shroud draped over everything.

“I brought Sergeant Winters with me today,” Keller said. “I thought you should meet. If you have any, uh, concerns, you can contact him. John, this is Gino and Rose D’Angelo.”

The men shook hands. Mrs. D’Angelo went into the living room.

“What sort of concerns might we have, Chief Keller?” Gino D’Angelo asked.

“Why don’t we have a seat,” Keller said.

Gino led the way into the living room. Keller threw Winters a grimace.

The chief sat down, but Winters chose to stand. The living room was furnished in long-out-of-date shades of brown and orange. He recognized a collection of dark green glass ornaments as similar to ones he’d seen when Eliza dragged him to an antique fair in the spring.

Gino helped his wife into a stiff-backed wooden chair, and then dropped himself into a worn, cracked La-Z-Boy that had the best view of the TV. Alone in this room, the TV was modern. A thirty-inch flat screen. At the moment it was playing a game show, the sound turned up so loud they’d have to shout to be heard. The room was stifling hot, smelling of dust and mold. The air conditioning was not on, there were no fans; the windows were closed.

Winters’ eyes were instantly drawn to the portrait dominating the room. It hung on the far wall, above the gas fireplace, showing a beautiful young woman on her graduation day. Her thick black hair, burnished to a high shine, fell in a waterfall past her shoulders, her olive skin was clear, her cheekbones prominent, her eyes a dark brown. Her smile was all-encompassing. One of her front teeth was slightly crooked, giving her a mischievous a

ir. She wore a mortar board and gown, and held her diploma proudly. So young, so beautiful. Looking bravely, hopefully, toward a future that would never be. If he’d come into this house unprepared he would have thought her a granddaughter. Maybe even a great-granddaughter, if Rose and Gino had had their own child when very young.

He looked away. An abundance of smaller pictures sat on side tables. Most of them were of children, a boy and a girl, growing up, the years passing. Several of a boy, then a man, changed as time marched on. Of the young woman on the wall, none of the pictures were more recent than her graduation.

The sound from the TV ended abruptly. Silence filled the room.

“My daughter, Sophia,” the woman said, her eyes fixed on Winters.

“She was…very lovely.”

“Yes.”

The police were not offered coffee or cold drinks. Keller coughed. “You’ve heard that Walt Desmond’s appeal was successful?

The man nodded. The woman’s eyes blazed fire. “So,” Gino said, “there will be another trial. Another ordeal for Rose. For me.”

“No. The Crown has decided not to retry the case. They have withdrawn all charges.”

“What does that mean?” Rose asked. “Gino, what is he saying?”

“It’s over,” Keller said, “There will not be a new trial.”

“It will never be over. Not for us,” she said.

“Mr. Desmond has been released from prison. I thought you should know.”

Rose moaned. Her husband leapt to his feet. “You people, you did this.”

“I…” Keller said.

“Your police didn’t work hard enough. You didn’t prepare a good enough case. You let this happen. What kind of a country do we live in where murderers…?”

“Please, Mr. D’Angelo,” Winters said. “Mr. Desmond has served twenty-five years and is now out of prison. Recriminations won’t help.”

“Twenty-five years. What is twenty-five years to us, but twenty-five years that our Sophia did not get to live?”

Silent Night, Deadly Night

Silent Night, Deadly Night Coral Reef Views

Coral Reef Views Deadly Summer Nights

Deadly Summer Nights Murder in a Teacup

Murder in a Teacup Whiteout

Whiteout Dying in a Winter Wonderland

Dying in a Winter Wonderland Tea & Treachery

Tea & Treachery Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen

Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery Body on Baker Street

Body on Baker Street Gold Mountain

Gold Mountain Blue Water Hues

Blue Water Hues Hark the Herald Angels Slay

Hark the Herald Angels Slay Murder at Lost Dog Lake

Murder at Lost Dog Lake Blood and Belonging

Blood and Belonging A Winter Kill

A Winter Kill White Sand Blues

White Sand Blues Scare the Light Away

Scare the Light Away Burden of Memory

Burden of Memory More Than Sorrow

More Than Sorrow In the Shadow of the Glacier

In the Shadow of the Glacier Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery

Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery Gold Web

Gold Web Haitian Graves

Haitian Graves Valley of the Lost

Valley of the Lost We Wish You a Murderous Christmas

We Wish You a Murderous Christmas Negative Image

Negative Image A Scandal in Scarlet

A Scandal in Scarlet Juba Good

Juba Good Winter of Secrets

Winter of Secrets Unreasonable Doubt

Unreasonable Doubt Gold Fever

Gold Fever Among the Departed

Among the Departed Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

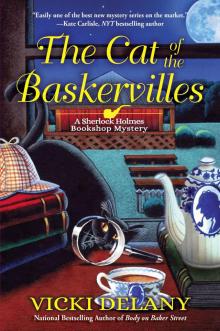

Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery The Cat of the Baskervilles

The Cat of the Baskervilles