- Home

- Vicki Delany

A Scandal in Scarlet Page 4

A Scandal in Scarlet Read online

Page 4

Donald Morris, prominent Sherlockian, was one of the last people to arrive. He had dressed for the occasion not in red, but in a brown suit under an Inverness cape. A gold-framed pin showing a silhouette of the Great Detective with his pipe was fastened to his chest.

“Aren’t you rather warm in that get-up?” I asked him.

“A gentleman dresses for the occasion, regardless of the weather,” he said.

I searched through my memory banks, trying to remember if that was a quote from Holmes. If it was, it was obscure, and my own knowledge of the canon isn’t that vast or very detailed.

I handed Donald a program. “Here for The Valley of Fear, are you?”

His narrow eyes glimmered. “I might have a mild interest.” He glanced around the room. His face fell when he spotted Grant Thompson taking his seat. Donald was a keen collector, but he didn’t have enough money to properly indulge his hobby. Grant, on the other hand, was a rare book dealer. He’d be prepared to spend whatever he thought he’d be able to sell the book for.

At quarter to five, every seat was taken, and all the program books had been handed out. At a signal from Jayne, the staff began serving tea. It wasn’t complicated. Each table was preset with milk and sugar for the tea, and pots of jam and clotted cream and a plate of butter for the scones. Two teapots were placed on each table: a red or pink one containing English breakfast and a green or blue with decaffeinated tea. I helped Fiona and Jocelyn serve the scones. I suffered no mishaps, and none of the precious baking hit the floor. Food served, I went into the kitchen and took off my apron, as did Jayne. Then she and I joined Leslie at the table of museum volunteers, while Fiona and Jocelyn kept an eye on the teapots. The room was fragrant with the scent of hot tea and scones warm from the oven. People laughed and chatted and served themselves food and drink. I noticed some people, with looks of intense concentration on their faces, jotting notes in the margins of their auction booklet.

Not everyone had worn scarlet but enough had, in one way or another, that the audience looked as though they were attending a Valentine’s Day party. The volunteers all had handcrafted corsages, made of red ribbon, pinned to their chests next to the museum’s small badge.

Jayne and I were seated at a round table that normally accommodated six. We’d been squeezed in tight to make places for eight. Some of these women were regulars to the bookshop, and I was introduced to the ones I didn’t know. One chair at our table was unoccupied. I glanced around the room. “Where’s Kathy?”

“She’s in the back doing a last-minute check,” Leslie said. “She told me to leave her alone.”

One of the volunteers was short and stout, with the round cheeks of a chipmunk and the twitchy, nervous mannerisms of a small animal venturing out of her nest for the first time. “I’m not surprised Kathy doesn’t want to come out,” she said. “There’s nothing she loves more than to be the center of attention, and that woman ruined her spotlight.” As one, the table turned to glare at Maureen leaning over the person next to her and waving her finger in the mayor’s face. Her Honor’s smile was fixed, and her eyes might have been rolling.

“Poor Kathy. She’s worked so hard for the museum,” another volunteer said. “We’re lucky to have her at this critical time. Can you imagine if Robyn were still in charge? She’d still be organizing committees and arguing over whether we need coffee and tea at the meeting or if coffee’s enough.” She put on a serious frown and a deep voice. “ ‘The twenty-second order of business will be to decide if two spoons of sugar per person are enough or if one will do.’ ”

Half the women at our table laughed. The other half scowled in disapproval. “Robyn might be a micro-manager,” Chipmunk-woman said, “but that’s only because she always wants the best. We all know she’s totally devoted to the museum. Kathy’s only in it for herself.”

“That’s unfair, Sharon,” someone said. “There’s not a lot of glory, and certainly no money, to be found in running a museum of our size.”

“Robyn was good at managing people,” said a woman with deep black hair sprayed into a stiff helmet. “Which can’t be said for Kathy, who’s driven many of the longtime stalwarts away.”

“Oh, pooh. That bunch of old biddies haven’t had a new idea in this century.” One of my store regulars laughed. “Heck, some of them probably hadn’t had a new idea in the last century either. Kathy brought in fresh new blood. I, for one, am glad we have her.”

“Speaking of Robyn,” Helmet-hair said, “she’s noticeable by her absence. I thought I saw her outside when I arrived.”

“You were imagining things, Barb,” Sharon said. “I’m not surprised she didn’t come. Robyn’s too proud to take a chance of Kathy humiliating her again.”

“If Robyn feels she was humiliated, it’s her fault,” Helmet-hair, aka Barb, said. “Kathy merely pointed out the obvious, that—”

“Let’s not squabble,” Leslie said. “Regardless of what you think of Kathy, she’s worked hard for this event, and she didn’t need a public spat with Maureen on top of all the gossip about her husband.”

“I can’t believe they had the nerve to show up here,” Sharon said.

“Disgraceful,” Helmet-hair said. The others nodded in agreement. Tea was poured.

“You mean Kathy’s ex-husband came?” I whispered to Leslie.

“Yup. That’s him and his paramour at the table nearest the bookshop door. Gray hair and glasses and sour faces. They do look rather alike, come to think of it.”

I had a quick peek. He had a thick mane of iron-gray hair curling around his collar and wore rimless glasses. Her white hair was cut short, and she peered myopically at the world through coke-bottle-bottom spectacles. If I didn’t know otherwise, I’d assume they were a many-years-married couple, judging by the way they sat in adjacent chairs but didn’t look at each other or say anything more intimate than “Please pass the milk.” He stared off into space, munching on a scone, and she scowled into her teacup. Neither of them had worn a drop of red, and they didn’t join the conversation at their table.

I didn’t recognize her, but I knew him. He was a bookshop regular, fond of Holmes pastiche novels, particularly ones that featured a twist on Holmes and Watson as we know them. His most recent purchase had been Sherlock Holmes—The Labyrinth of Death by James Lovegrove, but that was months ago. He hadn’t been into the Emporium for quite some time. I hoped he’d drive up the bidding on my basket of books.

Once the scones were but crumbs on people’s plates, and the jars of jam and Devonshire cream had been scraped clean, Jocelyn and Fiona went through the room one last time, offering fresh pots of tea. The plan was to have a short pause before the auction began. Give people a bathroom break and a chance to greet their friends or study the auction book in detail. I’d given the book a quick glance and had decided to bid on item number twenty-three, a pearl necklace. I didn’t need, or particularly want, a pearl necklace, but it was one of the few items I could comfortably afford, providing the bidding didn’t go too high. West Londoners had been extremely generous.

People were getting up from their seats and milling about. A few headed for the restroom, and some studied the teapots and tea paraphernalia we offered for sale. Of the two ropes decorated to make teapot chains Jayne had earlier hung on the wall, only one remained. Someone must have bought one already. Jayne would be pleased.

I leaned back in my chair and smiled at my friend. “That went well. The scones were delicious.”

She lifted her teacup in a salute. “Now that part’s over, I can relax and enjoy the auction. I see Rebecca Stanton and some of her crowd came—that should drive the prices up. Are you going to bid on anything, Gemma?”

“I might try for the pearl necklace. I could give it to my mother for Christmas. If I don’t get that, then maybe the dinner at the Blue Water Café. Speaking of which, how’s Andy?”

“He’s fine, I guess.”

“You guess? Don’t you know?”

“It’s summer

, Gemma. Andy’s busy with his business. I’m busy with mine.”

Jayne has asked me many times not to interfere in her love life. I have no intention of following those instructions. If things weren’t progressing to my satisfaction between Jayne and Andy, it was Jayne’s fault. The man adored her and was perfect for her, and at the moment she wasn’t seeing anyone. I decided to buy the dinner voucher and make her use it to treat Andy to a date at his own place.

The women at my table began talking about the things they hoped to get for the museum with the proceeds from the auction. Jayne excused herself to check on the kitchen. Leslie asked me if I’d heard from Arthur. After I’d given her his news, I glanced around the tearoom.

People were getting restless. More than a few had taken out their phones, and I noticed the mayor checking her watch. Fiona and Jocelyn were clearing empty teacups off the tables. Helmet-hair was tapping her teaspoon against the table in what was rapidly becoming a highly annoying rhythm. “We need to get things going,” I said to Leslie, “or people are going to start leaving.”

Leslie glanced around the room. “Kathy hasn’t come out yet. She said wanted to be left alone until it was time to begin.”

“You’ve left her alone for long enough. We need to get this show on the road.”

“Gemma’s right,” Barb said. “I feel sorry for Kathy over what happened, but we shouldn’t have to wait any longer for her to get out of her sulk. She can be a downright prima donna when she wants to be.”

I stood up. “I’ll check on her. I’ll tell her five minutes.”

I passed Maureen heading for her seat, and she gave me a sniff of disapproval. Then the swinging doors to the kitchen opened, and I skipped nimbly out of the way. “What’s happening?” Jayne said. “Are they starting?”

“I’m getting Kathy now.”

Jayne fell into step behind me. I turned the handle on the storage room and pushed it open. “Kathy, you need to get out there. People are getting restless.”

I stepped into the room. I stopped so abruptly that Jayne crashed into the back of me. “What’s the matter?” she said.

As well as the usual supplies for a busy bakery and restaurant, the room was full of auction items, everything from a woman’s winter coat to a gold and diamond necklace, to a concrete garden statue of a resting Buddha. Kathy Lamb lay on the floor among a scattering of broken miniature teacups. The pink rope that had tied the cups together was wrapped around her neck, and she did not move.

Chapter Five

“You again!” said Detective Louise Estrada.

“Sadly, yes. Me again,” I said.

“If you went back to England, the murder rate in this town would decline sharply.”

“I hope you’re not implying that I am personally responsible for everything that happens here. I shouldn’t have to point out to you, Detective, but I will—”

“Enough.” Ryan said. “Tell us everything that did happen here, Gemma.”

I leaned against the counter in the kitchen and sighed. When people said they wanted to know everything, they rarely did. Ryan looked at me with his beautiful blue eyes, the color of the ocean on a sunny day, and Estrada watched me with her dark ones, a hurricane fast moving inland. I took a moment to gather my thoughts.

When Jayne and I had burst into the storage room, I’d dropped to my knees beside Kathy and tore at the rope wrapped tightly around her neck. I could tell by the emptiness in her eyes and the still skin beneath my fingers that we were too late, but still I shouted, “Hand me those scissors!” to Jayne.

“What scissors?” she asked.

I’d noticed them when I’d been in the room earlier. “On top of the box marked lot 67.”

“Got them!” She pressed the cold steel into my hand. I cut the rope, and it fell away in a clatter of breaking china, but Kathy Lamb did not move.

“Call nine-one-one,” I said to Jayne. “Then get out there and tell everyone the auction has been delayed for a medical emergency. Ask Grant to guard the door. No one in or out until the police and ambulance get here.”

Jayne did as I’d asked, and I jumped to my feet and studied the room. The door to the back alley was unlocked. Interesting. Had it been left unlocked when the tea began, or had Kathy opened it to admit her killer? If the latter, it didn’t necessarily mean she knew that person. Many people open doors without checking who’s there, at least in the center of town in the daytime.

Although in this case thousands of dollars’ worth of goods were stacked in the room.

Nothing appeared to have been moved since I’d been here earlier, except for the arrival of Maureen’s painting, which stood propped against the wall next to a beautiful piece by a local artist who’d achieved some degree of international fame. The proximity did Maureen’s amateur attempt no favors.

The auction items were labeled and arranged in the order in which they would be presented. Envelopes containing gift cards or experiences were mixed in with the physical goods. The one in the front had the logo of the Harbor Inn. The auction book had told me the Inn was offering a fall weekend for two in the main suite, including one night’s dinner in the restaurant, for an opening bid of five hundred dollars. Next came my basket of Holmes goods, offered at two hundred and fifty. I’d been almost embarrassed when I’d seen its listing: it was the cheapest item there. Even dinner for two at the Blue Water Café, including wine with every course, was going for upward of three hundred dollars.

Mine was cheapest, that is, other than Maureen’s painting, for which Kathy herself had offered a buck fifty.

The most expensive item in the auction was the diamond necklace, opening bid fifteen thousand. It was lot number ninety, the final one. I spotted the small blue box and walked carefully through the room, trying to avoid disturbing anything, and opened it, taking care not to leave any fingerprints on the box itself. The necklace nestled within. Even in the dim light of the storage room, the jewels sparkled. In other circumstances, I’d take the time to admire it. Instead, I closed the box. The second most expensive item was lot number eighty-nine, Uncle Arthur’s copy of The Valley of Fear, with an opening bid of twelve thousand. The book was sitting where I’d put it. I tried to remember what other small, easily portable items had been listed. There weren’t many of those. Most of the expensive things were experiences, such as three days sailing offered by the West London Yacht Club for nine thousand. No thief would take a gift certificate and expect to cash it in without being caught.

Would they?

Ninety items had been listed in the auction program book; as far as I could tell with a quick look, ninety-one, including Maureen’s last-minute addition, were still in this room.

As I’d been checking out my surroundings, I’d been aware of the sound of rising voices coming from the tearoom. People were questioning what was going on.

Someone knocked on the door. “Gemma. It’s Jennifer Barton here. Can I be of assistance?”

I opened the door a fraction.

Jennifer stood in the doorway. More than a few curious faces attempted to peer over her shoulder.

“Come in, Doctor,” I said. “Mrs. Lamb has, uh, taken ill. Has someone called nine-one-one?”

“Yes. They’re on their way.” She came inside, and I shut the door firmly behind her against the babble of shouted questions.

Dr. Barton looked at the body on the floor. She looked at me.

“Dead,” I said.

“So it would appear.” She dropped to her knees beside Kathy Lamb. I could hear sirens approaching and a renewed buzz of voices from the tearoom.

“Through there,” someone shouted. Boots sounded on the floor.

“I’ll let them in.” I opened the door once again.

I slipped out of the storage room, past the paramedics and police officers filling the narrow hallway, and went back to the restaurant. A uniformed officer stood at the door while guests milled about. Blue and red lights flashed from the vehicles on the street outside. The curi

ous began to gather on the sidewalk. Inside, auction guests threw questions at the emergency personal or one another. A couple of women wept. Sharon spotted me and hurried over. “Is she okay? Kathy? What’s going on? I didn’t mean the things I said about her—really, I didn’t.” She twisted her hands, and her small eyes darted about.

“I’m sorry, but I don’t remember your name,” I said, which wasn’t entirely true.

“I’m Sharon Musgrave. I’m the bookkeeper at the museum, and I also volunteer in the kitchen. I wear a long dress and a bonnet and bake bread, and I—”

“Why don’t you go back to your seat, Sharon?” I suggested.

She ducked her head and tiptoed away.

“When’s the auction going to start?” The man standing in front of me was dressed in the best of Ralph Lauren summer-in-New-England wear. White trousers, navy-blue jacket with thin white stripe, blue shirt with white collar, red handkerchief in the jacket pocket, gold cuff links. Even blue canvas shoes worn without socks. “I don’t have all day here. I’ve got an important dinner meeting tonight.”

“I’m sure your dinner companions will understand that even yacht club business must wait for a medical emergency, Mr. O’Callaghan,” I said.

His eyes narrowed. “How’d you know I’m from the yacht club? And how’d you know my name? Have we met?”

“No,” I said. If his clothes and his attitude hadn’t told me he was with a yacht club, I’d earlier observed him pointing out item number seventy-four on the auction sheet to the elderly lady with the same close-set eyes and thin lips seated next to him at tea. His expression had been boastful, not hopeful, meaning he had contributed the item, not that he intended to bid on it. His gold cufflinks were monogrammed “JOC.” The commodore of the West London Yacht Club went by the name of Jock O’Callaghan. Great-Uncle Arthur, proud seaman, had been approached several times about joining the club. When he was being polite, he called the club in general, and Jock O’Callaghan in particular, “a bunch of stuck-up chinless twits.”

Silent Night, Deadly Night

Silent Night, Deadly Night Coral Reef Views

Coral Reef Views Deadly Summer Nights

Deadly Summer Nights Murder in a Teacup

Murder in a Teacup Whiteout

Whiteout Dying in a Winter Wonderland

Dying in a Winter Wonderland Tea & Treachery

Tea & Treachery Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen

Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery Body on Baker Street

Body on Baker Street Gold Mountain

Gold Mountain Blue Water Hues

Blue Water Hues Hark the Herald Angels Slay

Hark the Herald Angels Slay Murder at Lost Dog Lake

Murder at Lost Dog Lake Blood and Belonging

Blood and Belonging A Winter Kill

A Winter Kill White Sand Blues

White Sand Blues Scare the Light Away

Scare the Light Away Burden of Memory

Burden of Memory More Than Sorrow

More Than Sorrow In the Shadow of the Glacier

In the Shadow of the Glacier Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery

Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery Gold Web

Gold Web Haitian Graves

Haitian Graves Valley of the Lost

Valley of the Lost We Wish You a Murderous Christmas

We Wish You a Murderous Christmas Negative Image

Negative Image A Scandal in Scarlet

A Scandal in Scarlet Juba Good

Juba Good Winter of Secrets

Winter of Secrets Unreasonable Doubt

Unreasonable Doubt Gold Fever

Gold Fever Among the Departed

Among the Departed Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

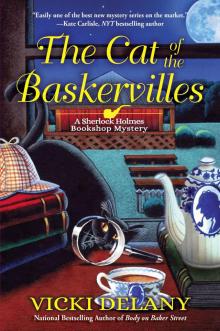

Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery The Cat of the Baskervilles

The Cat of the Baskervilles