- Home

- Vicki Delany

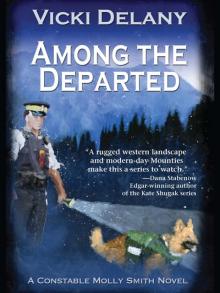

Among the Departed Page 3

Among the Departed Read online

Page 3

“Don’t remind me,” he groaned, “of what I missed because of this little guy.”

They returned Jamie to his relieved family and applauding onlookers. Norman got the lion’s share of the attention, which was fine with Smith. He’d done all the work.

After the dog had basked in the fuss and excitement, Tocek put him in the truck and pulled the Mountie who’d stayed with the family aside.

The man’s eyes opened wide. “You are kidding me?”

“Nope.”

“I’ll call it in.”

“What happens now?” Smith asked.

“Ron or Alison will come out in the morning, there’s not much of a hurry, and take a look. They’ll send it off to an expert somewhere for analysis. If the bones aren’t human they’ll call me nasty names. If they’re human but more than fifty or so years old, they’ll take them for a proper burial. And if not, then someone has a case. Are you, uh, coming back to my place?”

“Drop me at home, please. I’m bushed. That was emotionally draining.” She gave him a small grin. “Do you mind?”

“Yes, but tell you the truth, I’m done for too.”

“Officers.” Mr. and Mrs. Paulson came up to them. The purple-haired daughter, Poppy, with them. She ignored Smith and gave Adam a huge smile, ruined by the row of braces across her teeth. “We can’t thank you enough.” Emily carried Jamie so tightly she might have feared if she relaxed her grip he would disappear in a puff of smoke. He clutched the pink elephant.

“You saved our son,” Nigel said.

“It was our pleasure,” Smith said.

“He’ll be able to tell his friends at school about his great adventure,” Tocek said, trying to ignore the purple-haired girl’s adoring eyes.

“No more adventures for this family.” Nigel held out his hand, and Tocek and Smith shook. “Give that dog a big fat bone from us, will you, Constable?”

“Sure. Take care.”

“Nice to be thanked for doing our job for a change,” Smith said, buckling her seat belt.

Tocek put the truck in gear. “Yeah. I’ll let you know what they find out about those bones, if you’re interested.”

“I am.”

Chapter Four

Smith looked up at a tap on the door to the constable’s office. It was coming up to one o’clock and she was finishing her sandwich while doing paperwork before heading back out to the street.

“Hey, John,” she said.

“Heard you had a bit of off-duty excitement last week and went for a tromp in the woods,” Sergeant John Winters said.

For a moment she wasn’t sure what he was referring to. “Oh, right. Adam and the dog got a call for a little boy lost in Koola Park. Left his parents’ campsite to go looking for grizzly bears. It was incredible watching Norman work. He and Adam, sometimes it’s like they’re communicating telepathically.”

“Never fails to impress me, either. You were there when they found the bones?”

“I didn’t get much of a look, but Adam thought they might be human. Have you heard anything more?” She pushed her chair away from the computer and got to her feet.

“Ron and Alison are heading out there now. Ron got a call this morning from the forensic anthropologist at Simon Fraser University where he sent the bones. A preliminary test shows they’re human. I’m going out to have a look. Want to join me? Won’t be long. I have nothing to contribute at this stage.”

“Sure.” Walking the afternoon beat on Front Street in Trafalgar, British Columbia was one of the most boring jobs on earth. Until the bars got busy, and on a Tuesday they’d be quiet now that university students and summer visitors had headed back home. The most exciting thing that might happen would be a little old lady trying to parallel park her little old car and scratching the parking meter.

They took the detectives’ van and headed out of town. It was still summer in Trafalgar, but as they climbed into the mountains the few deciduous trees scatted among the evergreens began turning yellow and the temperature dropped. “Why did the Mounties call you? Do they think these bones have something to do with the city?”

“Just a courtesy. The person could have originated in Trafalgar.”

They parked at the same spot she and Adam had the previous week. She recognized the van belonging to Ron Gavin, the RCMP’s head forensic investigator for the area. The campsite was deserted, Jamie and his family long gone. She hoped they hadn’t given up on camping or the B.C. wilderness.

A line of yellow police tape had taken the place of discarded clothing, dog vests, and handcuffs leading to the bones.

Winters called out as they got near and Ron Gavin shouted in reply. Smith followed the sergeant to see a scene considerably different than the previous time she’d been here.

Although it was daytime, lights had been set up to break the forest shadows. The spot where they’d found Jamie was at the bottom of the mountain. A trickle of water wound its way down the slope, around rocks, leaking into the ground at the depression at the base of the red cedar. It had been a hot dry summer, and the stream was little more than a patch of wet ground. In spring it would be a fast-moving creek.

Corporal Alison Townshend, Gavin’s partner, knelt in the mud several feet up, her more than adequate butt greeting them. Her curly gray head was close to the ground and she carefully scraped at the dirt with a small trowel. She grunted something that might have been a greeting without bothering to look up.

“Human all right,” Gavin said. “Not ancient, either. On sight, old bones look much the same as more recent ones. It mostly depends on the environment they’ve been in. The people at the lab did their thing and that’s what they tell me. Adam pulled up part of a hand. We found three finger bones close by, and further up,” he gestured to his partner, “part of a long bone that might be from a leg.”

“Not much,” Smith said.

“We’ve got a lot of ground still to cover. We’re setting up a grid pattern and we’ll pretty much take this mountainside apart. At a guess, I’d say the excessive amount of snow we had last winter caused more flooding than normal and the bones washed down. So far they seem to be scattered up the hillside.”

“Age?”

“Adult, or near enough. Can’t tell gender, with nothing more to go on.”

Townshend grunted and straightened up. She leaned back on her knees. “Been dead for less than fifteen years.”

“Wow,” Smith said, starting up the hill. “You can tell that from the bones?”

“Hold it, Constable,” Gavin snapped. “Don’t take another step. You don’t know what’s under your feet.”

“Sorry,” she said, face burning. She retraced her path carefully.

“What you got, Alison?” Gavin asked.

She studied the objects in her hand. “There’s a bit of rotting cloth here, might be part of a pocket judging by the stitching. Doesn’t have to be from the same person of course, but it was caught on an edge of broken bone. In the cloth, I found this.” She held up a small, round brown object. “One Canadian cent. Issued 1995.”

“You might well have a case,” Winters said.

“I’ll assume that, until I get evidence to the contrary. I can’t get a signal in here, so can you call this in when you get in range, John?”

“Sure. Come on, Molly. Back to work.”

“What now?”

“You, to the streets. Me, into the dust of the missing person files.”

***

Lucky Smith had never been fond of the police. Sure, they were necessary to keep the peace, to keep people like her safe in their homes and businesses, knew they worked hard at a difficult job with few thanks and not a heck of a lot of money.

But she was an old hippie at heart and had never forgotten, nor forgiven, the mean bastard of a Chicago cop w

ho’d smacked her across the back of the neck with a truncheon, with no provocation whatsoever, and tossed her into a paddy wagon after the police ran amuck at the Democratic convention in 1968. Or even here in peaceful Trafalgar, the ones who arrested people for merely sitting on public benches, smoking a joint. Or burned out a crop of healthy plants that were intended to be turned into a product which did a lot less harm than alcohol or cigarettes.

And when she heard about police officers using Tasers on innocent civilians, sometimes even children, it made her blood positively boil.

But today, when the police officer came into her shop, dressed in the dark blue uniform, bulky Kevlar vest with POLICE in big threatening words across the back, the overloaded equipment belt jangling with the menace of physical force, it was hard to get too angry.

Lucky leaned over and accepted a kiss on the cheek. “You look tired, have you been getting enough sleep?”

“I’m fine, Mom.” Molly Smith pulled off her hat and rubbed at her hair. Lucky was pleased to see that the short spikes were growing out. Before too much longer her daughter would have to tie her blond hair back into a pony tail. “Had a bit of excitement last week when Adam and the dog were called out to search for a missing child.”

“Oh, dear, poor thing. Did they find her?”

“It was a boy. Norman found him safe and sound, disappointed he hadn’t seen a grizzly.”

“That dog does such a good job. Too bad about the time he bit that man who was…”

“You mean the man who was threatening to slice up his former boss with a chef’s knife? Give it up, Mom. Norman does a good job period. As does Adam and as do I.”

Lucky mumbled her agreement.

“I swear, Mom, ever since Dad died you get more and more sentimental about the golden olden days when you and Dad were against the world and the fascist police were on the other side.”

“I do not.”

“I came to take you on a trip down memory lane. Do you have a few minutes?”

“Pull up a seat.” It was almost closing time during the shoulder season between summer hiking and kayaking and winter skiing. Unlikely anyone would be coming into the store. Lucky flipped the sign hanging over the door to closed before heading for the stool behind the counter. Her daughter glanced at a skiing magazine, and Lucky smiled to see traces of longing cross Moonlight’s pretty face.

Moonlight was the girl’s name. A beautiful, soft, romantic name that she’d decided wasn’t suitable for a police officer, and thus started calling herself Molly.

“Only a couple more months,” Lucky said, tapping the face of the magazine with a badly chewed fingernail. “And you’ll be back on the slopes.”

“Don’t know if I can wait that long. Tell me what you remember about Brian Nowak.”

“Good heavens, that is a trip down memory lane. You were friends with his daughter, what was her name?”

“Nicky.”

“Yes, Nicky. What’s she doing now?”

“She quit school before graduation and left. I lost contact.”

“I see Marjorie sometimes, in town. She’s like a ghost of her former self. I tried to encourage her to keep coming to the youth center or to join the African grandmothers’ group, but she seemed to want to fade away.”

“You weren’t friends though, not that I remember.”

“No. I tried to make friends after, but she rebuffed me. Come to think of it, it’s been a long time, more than a year at least, since I’ve seen her. I wonder if she’s still in Trafalgar.”

“Nicky had an older brother, didn’t she?”

“Kyle. People still talk about Kyle. He’s an artist who almost never leaves the house, except at night.”

“We, the police, know him. I’d forgotten he was Nicky’s brother until today. He hangs around the streets at night like you said, but never gets himself in any trouble.”

“Why are you asking? Has something new been discovered?”

“Perhaps. Mr. Nowak disappeared in ’96.”

“I don’t remember exactly, but that sounds about right.”

“Don’t gossip about this Mom, okay? It will be in tomorrow’s paper, so keep it under your hat until then.”

Lucky nodded. As if she ever gossiped.

“The night we found the missing boy, Norman dug up some bones, human bones.”

“You think…”

“We don’t think anything, yet. It might be that the bones are from someone who was alive in 1995. Obviously, the forensic guys have work to do to be sure, and so far we’ve only got a few hand bones and part of a leg, which isn’t much. John Winters has sent over to city hall where they keep the old boxes of statements and case notes, and is probably down in the basement now digging through old evidence files. I thought of Mr. Nowak right away. I was in grade eight, so it would have been in ’96 when he disappeared.”

Chapter Five

“Why would a daddy leave home?” Moonlight asked between spoonfuls of homemade granola. At Nicky’s house they ate store-bought cereal. Count Chocula and Fruit Loops and Sugar Puffs. Good stuff that turned the milk all sorts of yucky, fun colors. At the Smith house they ate granola made by their mother and never got store-bought cookies, either. And no matter how much Moonlight begged, Mom refused to buy chocolate milk.

She looked up in time to see her parents exchange a glance. “Well,” she demanded. “Why? Mr. Nowak ran away from home. I thought only kids did that.”

“Mr. Nowak’s a jerk,” her brother said.

“Samwise,” Mom snapped. “Don’t talk about things you don’t understand.”

“Is that what they’re saying at school?” Dad asked. “Mr. Nowak ran away?”

“Meredith told everyone Mr. Nowak ran away because he couldn’t stand being Nicky’s father any more.”

Sam laughed so hard he almost sprayed milk across the kitchen.

“Meredith Morgenstern is a common-or-garden gossip,” Mom said. “Not to mention a troublemaker. That’s pure nonsense.”

“No one knows what’s happened to Mr. Nowak, Moonlight.” Dad got up from the table and gave his wife a kiss on the top of her red curls. He was tall and Mom was short. Moonlight was only in grade eight, but she’d already passed her mother’s height, and Sam at seventeen was almost as tall as Dad. His running shoes were the size of boats. “See you at the store, dear. You kids have a good day at school.”

“As if that ever happens,” Sam said, rolling his eyes.

Dad took his keys down from the hook by the door. Jerome, the big shaggy retriever, sensed someone was leaving the house. He lumbered to his feet, but Mom said, “No,” and Dad shut the door behind him.

“Finish your breakfast. The bus will be here in ten minutes.”

“Why can’t we live in town, like Nicky does?” Moonlight asked. “So I can walk to school.”

“You know what, Moon,” Sam said as a sudden light came into his eyes. “If Mom would let me use her car, I could drive you to school every day.”

“Don’t put ideas in your sister’s head.” Mom poured the last of the coffee into her mug and switched off the pot. “You know that’s not going to happen.”

“So, where’s Mr. Nowak?” Moonlight said. “If he isn’t home?”

“He’s missing, dear. No one knows where he is.”

“That’s what missing means,” Sam explained.

Jerome lifted his head and barked, and moments later they heard a car coming up the long driveway. Lucky turned to look out the window. “Your father must have forgotten something. Oh.”

Moonlight jumped to her feet and ran to the window. “Neat. A police car.”

Mom was standing in the doorway, hands on hips, guarding her threshold by the time the car pulled to a stop and a man got out of the passenger seat. To Moonlight

’s disappointment he wasn’t wearing a uniform or carrying a gun on his hip.

“Sergeant Keller,” Mom said. “What are you doing here? The judge said I didn’t…”

“I’m not here about that, Mrs. Smith. Is your daughter still at home?

“Moonlight? Yes, but the school bus will be here in a few minutes.”

“It won’t take long.”

Mom stood back and the man came into the kitchen. He said hi to Moonlight and Samwise but looked at Mom.

“Samwise, go upstairs and get ready for the bus.”

“But…”

“Now.”

Sam left. Mom planted herself against the kitchen counter, arms crossed over her chest, a scowl on her face. Moonlight wondered why she didn’t offer to make the visitor coffee or bring out cookies. Uninvited, the man sat in Dad’s chair.

“Moonlight,” he said. “I’m Sergeant Paul Keller, with the Trafalgar Police.”

“I know.”

“I need to ask you some questions about your friend Nicky’s father, Brian Nowak.” He glanced over his shoulder. Mom’s face relaxed a bit. “Go ahead,” she said. “Bad business to be sure.”

“Okay,” Moonlight said.

“You were at the Nowak house last week. Having a sleep over, is that right?”

“Yes,” Mom said. “Saturday night.”

“If you don’t mind, Mrs. Smith, I’d like Moonlight to speak for herself.”

Moonlight hid a grin behind a glass of milk. Mom did sometimes think she could answer for her children. Even now that Moonlight was thirteen—a teenager!

“I slept over, yes.”

“Was Mr. Nowak at home?”

“I think so.”

“Are you sure?”

She thought. “Yeah, he was there.”

“Bye, Mom.” The front door slammed as Sam left for school. Moonlight hoped she’d be talking to Sergeant Keller long enough that she’d miss the bus. Maybe she’d get a ride in the police car. Wouldn’t that be great; they’d turn the lights and sirens on and all the kids would see her getting a ride as if she was a celebrity or something.

Silent Night, Deadly Night

Silent Night, Deadly Night Coral Reef Views

Coral Reef Views Deadly Summer Nights

Deadly Summer Nights Murder in a Teacup

Murder in a Teacup Whiteout

Whiteout Dying in a Winter Wonderland

Dying in a Winter Wonderland Tea & Treachery

Tea & Treachery Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen

Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery Body on Baker Street

Body on Baker Street Gold Mountain

Gold Mountain Blue Water Hues

Blue Water Hues Hark the Herald Angels Slay

Hark the Herald Angels Slay Murder at Lost Dog Lake

Murder at Lost Dog Lake Blood and Belonging

Blood and Belonging A Winter Kill

A Winter Kill White Sand Blues

White Sand Blues Scare the Light Away

Scare the Light Away Burden of Memory

Burden of Memory More Than Sorrow

More Than Sorrow In the Shadow of the Glacier

In the Shadow of the Glacier Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery

Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery Gold Web

Gold Web Haitian Graves

Haitian Graves Valley of the Lost

Valley of the Lost We Wish You a Murderous Christmas

We Wish You a Murderous Christmas Negative Image

Negative Image A Scandal in Scarlet

A Scandal in Scarlet Juba Good

Juba Good Winter of Secrets

Winter of Secrets Unreasonable Doubt

Unreasonable Doubt Gold Fever

Gold Fever Among the Departed

Among the Departed Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery The Cat of the Baskervilles

The Cat of the Baskervilles