- Home

- Vicki Delany

Deadly Director's Cut Page 2

Deadly Director's Cut Read online

Page 2

I watched him go. He’d been right about one thing: this hotel is all Olivia has left in the world, and it provides the livelihood of me and my aunt Tatiana. So far we’re squeaking by and even running a small profit, but the hotel business is high-risk, and a seasonal resort even more so.

Richard Kennelwood, son of the owner of the neighboring hotel, had suggested the film crew work here, and I was more than grateful.

The substantial fee WolfeBright Pictures was giving us in order to film on our property would give us a comfortable amount of breathing room. Aside from the direct fee, word had quickly spread that we had movie people here, and reservations were pouring in from outside for our restaurant and ballroom as people hoped to get a glimpse of the stars. First thing this morning, I’d been told all seats at dinner were taken for the rest of the week, and we’d be squeezing them into the early-evening cocktail hour and the late-night entertainment.

Income was good, but a full hotel meant more work for me, and I’d better get back at it. I turned around quickly, in time to see rows of faces peering out the front windows. Some of the staff didn’t duck fast enough, and they got the full force of my disapproving stare.

The door leading to the business offices and the kitchen areas are on one side of the lobby, tucked under the sweeping staircase leading to the grand ballroom and the more intimate dining and reception rooms. I crossed the lobby as fast as I could, dodging suitcase-laden bellhops, overexcited children, activities coordinators trying to corral overly excited children, gossiping women (“They say she’s been seen . . .”), gossiping men (“Not for me to say, but I heard . . .”), complaining teenagers, couples arguing over whether they wanted to play handball or attend the dance classes, and all the cacophony of weekend arrival and departure in the Catskills.

As I passed the bell desk, the man behind it was saying into the phone, “But I don’t have anyone.” He saw me, and a look of sheer relief crossed his face. “Okay. Got it.” He hung up and waved me down. “Mrs. Grady. A moment.”

“Yes?”

“Switchboard has a long-distance call for Mr. Th—Th . . . The movie guy.”

“Mr. Theropodous, what of it?”

“We’ve turned off the loudspeakers down by the dock. You said that was okay, right?”

“While they’re filming there, yes.”

“So switchboard can’t call him to the phone. They want me to send a page, but . . .” He looked around him and shrugged. “I haven’t got anyone right now.”

“Can’t the switchboard tell them Mr. Theropodous will call them back?”

“Caller says, ‘Right now. And make it snappy. Time is money, and so is a call from Hollywood.’ I was wondering if you . . .”

“Okay. I’ll run down and get him.” I turned and headed back across the lobby. I’d already lost one bellhop to be Elias Theropodous’s personal runner, and now I was expected to play message boy.

Time might be money, and the Hollywood executives might not be happy at holding on the phone line, but I didn’t think Elias would be any happier at being interrupted in the middle of a scene. I was going to whisper the message to the gum-chomping assistant director, standing close, but not too close, to the great man, but I found myself momentarily mesmerized by the activity. There truly is something captivating about seeing movie magic being made. The cameras were rolling, Elias leaning forward in his chair, his hands on his knees, watching intently.

Gloria Grant lifted her arms, and the emerald-green silk of her dress flared around her. She cried, “This is a mistake, Reginald. You’ll regret it for the rest of your life.”

Hadn’t I heard that very same line a while ago?

“I have to take a chance, Grandmama,” the young man exclaimed. “Surely you, of all people, can understand that.”

“I’ve made mistakes, Reginald,” Gloria declared. “Dreadful mistakes. I don’t want to see—”

“Stop. Stop.” Elias leapt to his feet. He was a large man, tall and heavyset, with a formidable presence.

“Gloria, I have told you and I have told you. You’re sounding regretful at having to tell him no. I don’t want regret. I want rage!”

Gloria’s eyes flared. “And I have told you and told you, Elias. This character’s a woman of depth, of years lived. She needs to bring her full range of human experience to dealing with her wayward grandson. She herself—”

“I don’t want her life history, Gloria. I want you to do what I’m telling you to do.” He swore loudly and heartily.

Some of the onlookers gasped in shock. A woman covered her son’s ears. Too late, I thought.

I stepped forward and cleared my throat. “Mr. Theropodous?”

He swung around and glared at me. “Who are you, and what do you want?” His brown eyes were small and close together, his prominent nose lined with rosacea. His fleshy jowls wobbled when he talked, making me think, for one brief moment, of Winston, my aunt Tatiana’s bulldog.

“Uh . . . I’m Elizabeth Grady? Manager of Haggerman’s? Olivia Peters’s daughter? We met when you arrived?”

“Can’t you see I’m busy?”

“You have a phone call. From Hollywood. They say it’s urgent and don’t want to wait until you have a chance to call back. They’re still on the line.”

“Always something. Very well. We’ll take a break. Fifteen minutes, people. And you”—he stabbed a finger at Gloria—“think about what I said. We do things my way here, and if that’s not okay with you . . . you aren’t the only old broad in Hollywood.”

Gloria’s face tightened with such anger I feared her makeup would crack. “Good luck finding someone else to step in at this point in time, Elias. How long do we have the use of this nice hotel for our filming? Less than a week, and then we’re back to a sound stage.”

Rather than reply, Elias snapped at me. “Where’s the nearest phone?”

“I’ll show you to the writing room. It’s usually quiet in there at this time of day.”

“It had better be. I’m not broadcasting my business to everyone in the mountains. Gary, get this scene rearranged. The sun’s moving. I hate filming on location.”

He stalked off, and I scurried along behind. Gordon, the bellhop assigned to be the director’s runner, scurried after me.

I showed Elias to the writing room. As expected it was empty. On rainy days guests come here to play cards or board games or to write letters. I picked up the phone and pressed the button and told the switchboard operator I had Mr. Theropodous on the line. Then I handed him the receiver and left the room.

“This better be important,” I heard him growl.

I shut the door behind me. “How’s it going down there?” I asked Gordon.

“As Shakespeare says, ‘Much ado about nothing.’ ” He shrugged. “I studied for a degree in English lit before the war. I wanted to be a college professor. But, well, the war happened.”

It happened to all of us, I thought. Some far worse than others. I didn’t ask him why he hadn’t gone back to finish college.

“The lady says her lines. The director yells at her and says she did it wrong, so she says them again, exactly the same as before. Then the guy says his lines, and the director tells him he did it wrong, so he says them again, and the director says that’s much better, even though I didn’t see any difference.”

“Outrageous!” Elias’s voice leaked through the solid wooden door to the writing room. “Impossible! Do you want an Academy Award–worthy production or a high school play on film?”

A moment later the door flew open and Elias stormed out. He pushed past Gordon and me without a word. He shouted at two women fresh from the beauty salon, chatting happily and walking slowly, to get out of his way. They leapt aside and clutched their purses to their chests in terror.

Chapter 2

My mother, Olivia Peters, had been a Broadway and Hollywood dance star. The professional life of a dancer isn’t long, and after one injury too many she’d been forced to retire. When she unexpectedly inherited Haggerman’s Catskills Resort from an unknown admirer, she managed to convince me to move to the Catskills with her and run the hotel for her.

I’d been raised above a corner shop in Brooklyn and spent most of my adult life living in Manhattan walk-ups. I’d moved to the mountains with a great deal of trepidation, but I soon found that I like it here. I like it a lot. When I can get time to enjoy it, which over the summer isn’t often.

I left my office at five thirty and went upstairs to check on preparations for this evening’s cocktail party. Rosemary Sullivan, our manager of food service, was putting the finishing touches on the bar supplies as I came in. I popped a green olive in my mouth and asked, “All under control?”

“Need you ask?” she said.

“No. But I’m asking anyway. Where’s the food?”

At that moment, the doors flew open and waiters carried in platters piled high. Tonight guests would munch on pigs in blankets, smoked oysters on toast, deviled eggs, small tomatoes with mayonnaise in the center and a shrimp placed on top, celery filled with a line of Cheez Whiz, fruit on skewers, squares of cheese stuck into a pineapple, and plenty of pickle trays. The cocktails would be as served in the most fashionable nightclubs of New York City. As well as managing the dining rooms and everything to do with the serving of food, outside of the realms of the chef and saladman, Rosemary worked as a bartender because she liked doing it and was good at it.

“Look at that,” she said with a laugh. “All you have to do is say the word and things happen around here.”

“Don’t I wish. Have a good night.”

“Are you co

ming back?”

“I don’t intend to. I’m having dinner with Olivia and her guest, and I’d like to get what passes for an early night after that. Not that I get much sleep on Velvet’s floor.”

“I’d invite you to share my room, but I have even less space than Velvet.”

Next I stopped in the main kitchen to check on dinner preparation. The scene of total and complete chaos told me everything was proceeding as normal. Chef Leonardo, aka Leon Lebowski, bellowed at me and waved a meat cleaver in my general direction. “You! Have you come to chop vegetables? To gently stir the roux until it is at the perfect consistency? To wash the pots and pans?”

“No.”

“Are you here to finally fire that useless saladman?”

“No.”

“Then get out!”

I did so. In the main dining room the waitstaff was laying the tables. They didn’t need any help from me either, so I walked across the big room, through the closed doors, and into the busy lobby. On a Sunday evening weary guests were checking in amid piles of luggage, excited children, and overly tired babies.

“We have a lake view, right? We specifically asked for a lake view.”

“Yes, Mrs. Cohen. Room 328 is one of our best suites, with a gorgeous view.”

Of course all our rooms were “one of our best,” and sometimes the “gorgeous view” was of a patch of trees.

“I want extra towels in our room. Last year there were not nearly enough.”

“I’ll instruct housekeeping, Mrs. Fitzpatrick.”

“We expect Jenny to be caring for the children on our stay. She did a good job last year.”

“I have a note on your registration card to that effect, Mr. D’Angelo.”

I kept walking and managed to get out the door before anyone called for my help.

Outside, bellhops were unloading cars and ferrying mountains of luggage into the lobby or down the path to the lakeside cabins. The movie crew had packed up for the day, and the guests were once again going about their regular activities. On the lake, orange paddleboats steered for shore and rowboats headed out to try their luck at catching a fish. Mothers or hotel-provided nannies gathered the last of the children out of the pool or the lake. A handball game was underway, and next to the tennis court two elderly men were bent over a game of chess. I’d swear those two never moved, except to come in for meals. Their conversation never changed either.

“McCarthy’s got the commies on the run,” one said.

“He’s gone too far,” the other replied.

“Check,” said the first.

I chuckled and carried on my way.

As I passed cabin four, I heard the sharp growl of my head gardener and stopped to see what was happening. Mario’s a big guy, and he loomed over Francis Monahan, garden assistant.

“Is something the matter?” I asked.

They both turned. At the sight of me, Francis released most of the tension in his neck and shoulders.

Francis is a shy, nervous man with a stutter, still traumatized by his wartime experiences and subject to bullying by some of the other staff. Not entirely willingly, I’d taken him under my wing, and I tried to look out for him without stepping on the toes of his immediate supervisor. He’d originally been employed as a dishwasher. After one catastrophe too many Rosemary had wanted to fire him outright, but I intervened to move him to a position that had less contact with fragile crockery and glassware.

“If there’s a problem, Mario,” I said, “you don’t discuss it with the staff within possible hearing of our guests.”

Mario looked around. “Don’t see no guests.”

“You know what I mean. What’s the problem?”

“The garden shed was left off the latch this afternoon.”

Francis mumbled something about not him.

“Is it secure now?” I asked.

“Yeah,” Mario said.

“Then we’re okay, aren’t we? Francis will remember to shut it properly next time. Was anything taken?”

“Weren’t me,” Francis muttered.

“Not that I can see,” Mario said in answer to my question. “But we can’t have people, guests or staff, wandering in willy-nilly.” He pointed to the fierce set of garden shears in Francis’s hand. “Dangerous places, gardens. Saws, scissors, axes, fertilizer, rodent traps, poison.”

“We definitely don’t want the guests hearing that we have a rodent problem,” I said. “Do we? Have a rodent problem?”

“Squirrels climb in open windows and chew the wiring, mice get in the flour bins in the kitchen and into the bathroom in guests’ rooms. Guests don’t like seeing mouse droppings.”

“I’m sure they don’t. I noticed disturbed earth in the flower beds earlier, as though something had been tunneling beneath the soil. Do you know what caused that?”

“Moles. We’ve laid down poison. Like I said, dangerous places gardens, and we can’t have people poking around where they’re not wanted.”

“Francis says he didn’t leave the door unlatched, so please don’t accuse him if you don’t have proof. Do you?”

Mario glanced at the younger man. “No.”

“You can carry on with what you were doing, Francis,” I said.

“Yes, m’m.” He bolted before I could change my mind.

“I’m sure a reminder notice posted on the inside of the door will help the problem,” I said. “Otherwise, how’s Francis working out?”

Mario took off his cap and rubbed at the top of his head. “Okay. He’s a good worker, Francis, tries hard, but he needs a lot of direction. No initiative, you know. Before you say it, I shouldn’t have assumed he’s the one who left the door off the latch. Any one of the guys could have done it, but they’ve all left for the day, so I had no one else to yell at.”

“You can’t lock it?”

“We lock it overnight, but I can’t have assistant gardeners wasting time trying to find me because they forgot their watering can.” He grumbled and started to walk away. He didn’t get far before he stopped at a pot of geraniums and plucked off yellowing leaves and dying blooms.

* * *

* * *

My mother and I live in a small house nestled in the woods at the edge of the property. It gives us some privacy, but it’s close enough that I can get to the hotel in minutes in case of an emergency. I turned at the end of the lakeside path and headed up the hill toward home, looking forward to a relaxing evening for a change. The path narrowed when it reached cabin nineteen and the sign clearly marked staff only. The dark woods closed in around me. The sounds of the lake and the busy resort fell away, and I breathed deeply, enjoying the scent of pine needles, thick undergrowth, pure clean air, and fresh water.

As I approached the house a furious chorus of barks began, and a woman’s sharp voice said, “Calm down, Winston. It’s only Elizabeth.”

“Only Elizabeth,” I said, as I climbed the steps to the porch. “What a greeting.”

My mother and her guests smiled at me, and my aunt Tatiana said, “You know what I mean, lastachka.” She’s always called me her little swallow.

“I hope that empty glass is for me,” I said.

“It is.” My mother reached for the pitcher of martinis and poured me a generous amount, and Aunt Tatiana added two plump olives. I accepted the glass and dropped into a vacant chair with a sigh. Olivia was dressed in white pedal pushers and a blue-and-white-checked blouse with the collar turned up to frame her beautiful face. Her black hair was swept back into a chignon, her dark eyes rimmed with mascara, her lipstick a pale pink matching the polish on her fingers. Tatiana had dressed to have dinner with her sister’s guest in a blue housedress that might have been new before America joined the war, thick dark stockings, and heavy-soled brown shoes. As usual she wore no makeup and her only jewelry was the thin gold wedding band she never took off.

I don’t think Aunt Tatiana has worn lipstick since her wedding day.

“Miss Grant was telling me about the hours and hours she has to spend in makeup to look natural for a single minute in front of the camera,” Velvet said. She’d changed into slim-fitting pink slacks and a pale green shirt. She looked cool and comfortable, unlike me with my girdle and stockings sticking to my hips and legs, sweat soaking into my bra, and my poodle haircut badly in need of refreshing, if I can ever find time to get to the hotel’s beauty salon. Like Lucille Ball, I have curly red hair, thus I’ve copied her hairstyle. It looks better on Miss Ball.

Silent Night, Deadly Night

Silent Night, Deadly Night Coral Reef Views

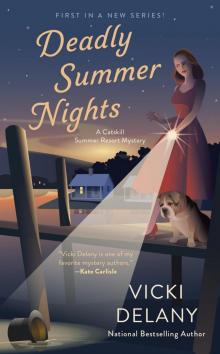

Coral Reef Views Deadly Summer Nights

Deadly Summer Nights Murder in a Teacup

Murder in a Teacup Whiteout

Whiteout Dying in a Winter Wonderland

Dying in a Winter Wonderland Tea & Treachery

Tea & Treachery Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen

Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery Body on Baker Street

Body on Baker Street Gold Mountain

Gold Mountain Blue Water Hues

Blue Water Hues Hark the Herald Angels Slay

Hark the Herald Angels Slay Murder at Lost Dog Lake

Murder at Lost Dog Lake Blood and Belonging

Blood and Belonging A Winter Kill

A Winter Kill White Sand Blues

White Sand Blues Scare the Light Away

Scare the Light Away Burden of Memory

Burden of Memory More Than Sorrow

More Than Sorrow In the Shadow of the Glacier

In the Shadow of the Glacier Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery

Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery Gold Web

Gold Web Haitian Graves

Haitian Graves Valley of the Lost

Valley of the Lost We Wish You a Murderous Christmas

We Wish You a Murderous Christmas Negative Image

Negative Image A Scandal in Scarlet

A Scandal in Scarlet Juba Good

Juba Good Winter of Secrets

Winter of Secrets Unreasonable Doubt

Unreasonable Doubt Gold Fever

Gold Fever Among the Departed

Among the Departed Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery The Cat of the Baskervilles

The Cat of the Baskervilles