- Home

- Vicki Delany

Blood and Belonging Page 2

Blood and Belonging Read online

Page 2

The police college in Haiti. No more than a couple of months ago. The graduation ceremony. Lines of new recruits, all of them fresh-faced and shiny. Their families, dressed in their best clothes, beaming with pride. Government officials trying not to look at their watches. Me, melting in the hot tropical sun.

He’d been dazzling in his dress uniform. Hat straight, buttons polished to a shine that rivaled the sun. Shoulders sharp with pride. His face split by a huge smile. His grip firm in mine as I offered my congratulations.

The dead man was PNH. A Haitian police officer.

THREE

“Robert Savin. Find out what you can about his current whereabouts, will you?”

“Why?” Agent Pierre Lamothe said.

“I think he’s here in Turks and Caicos.”

“Are you not having a good vacation, Ray? Is your wife angry with you? Are you looking for something to do?”

“Just find out, will you? Please.”

I was in Turks and Caicos for two weeks’ vacation. I wouldn’t have chosen a Caribbean holiday myself. But it had been a long, cold, snowy winter in the mountains of British Columbia where Jenny lives. She was desperate to feel the heat of the sun and see bright colors and green plants. I get enough heat and vegetation, thanks. I’m currently assigned to the UN police in Haiti. In Haiti, I live in a house with a big swimming pool. A gardener takes care of the garden and pool, and a maid tidies up after me. I head for the beaches on the north shore of Port-au-Prince Bay on the weekends. I wanted to go home to Canada for my vacation. See pine trees and snow. Feel cold, crisp air on my face. Ski powder during the day. Drink hot buttered rum and mulled wine in front of a roaring fire at night. But the last thing Jenny wanted was snow. My family can’t live with me in Haiti because it’s considered too dangerous. As it is, Jenny’s not happy with me working for the UN and living away from home all the time. It’s been hard on our marriage. It was time for me to make some sacrifices. So here we were, staying at a luxury hotel on the world’s best beach.

And now here I was, wondering why a Haitian cop had washed up on a Grace Bay beach.

“What would Savin be doing there?” Pierre asked.

That, I thought, was precisely the point. What would a Haitian police officer be doing in Turks and Caicos? What would have put him on an overcrowded refugee boat? And, most of all, why would he end up dead? “Look, Pierre, I’m not positive it was Savin I saw, but I’m pretty sure. In case I’m wrong, I don’t want to get anyone worried or upset. Just find out if he’s at work, will you. And if not, when he last was seen.”

I wasn’t wrong. It had been Savin, all right. I was positive of that. Not only did I recognize the dead man, but I now remembered meeting the young man in the photograph.

My job in Haiti is to help train the police. Mentor, advise, educate. I had worked with Agent Pierre Lamothe when I was training active duty officers. I gave them classroom instruction in the police station as well as following them on the streets. Then I was assigned to the police college to teach new recruits. Generally, I found the men and women eager to learn and keen to make a difference in Haiti. Robert Savin had been one of the best. A sharp intelligence, a keen love of his country and a firm dedication to the job. He’d graduated top of his class. I’d been proud to shake his hand.

Entire families had turned out for graduation day. Everyone scrubbed and polished and dressed in their best clothes. Suits and ties for the men, dresses and heels for the women. Boys wore starched white shirts, and girls had tied masses of colorful ribbons in their hair. The mood had been good. Upbeat and optimistic. Everyone happy and proud. Savin had introduced me to his much younger brother. Their parents had been killed in the earthquake. Robert had been left to raise his brother by himself.

Unlike most of the relatives, the younger brother looked like a typical American teenager. Baggy pants and unkempt hair. All attitude. Swaggering and smirking. A barely controlled sneer at me, the white man in uniform. But, try as he might, the boy couldn’t hide his pride in his brother. There had been a cousin as well, I remembered. A boy about the same age as Savin’s brother. We’d chatted briefly after the officials had fled and the family groups were breaking up. The boys asked me if I was from Los Angeles. I said British Columbia, but to them it was all the same. The United States or Canada. Streets paved with gold. Every black man loaded with bling, driving a convertible with a hot chick by his side. The brother told me he was a rap singer. He swung his skinny hips, pouted and made strange hand gestures. I pretended to be impressed. He was headed to L.A., he said, ready to make it big. His cousin nodded enthusiastically.

“Plenty of time for that,” I said. “Finish school first.”

“That’s what Robbie says,” the brother grumbled. “School’s a waste of time, man. I gotta take my chances when I can. The world’s not waiting for me to finish school.” We spoke French mixed with Creole. The boy didn’t have much English. I tried to point out that he’d need good English in Los Angeles. He shrugged, not much caring what I had to say.

We were interrupted by another of my students, asking me to pose for a picture with her parents. When we finished, Robert Savin’s brother and cousin had disappeared. I wished him well and moved on to chat with more people. I’d thought no more about him.

I was thinking about him now. “Savin has a brother,” I said to Pierre. “I don’t remember his name. Fifteen, sixteen maybe. Their parents are dead. See if you can locate the brother.”

Pierre sighed. “All right, Ray. When I have the time.”

“Sorry,” I said, “but that’s kinda the problem. I’m only here for another week. I need that info soonest.”

“Only for you, Ray,” he said. “Only for you. I’ll call you as soon as I know anything.”

“Thanks,” I said. “I’ll buy you a beer.”

“You’ll buy me more than one.” He hung up.

I chuckled.

The bathroom door opened, and my wife came out. “Who were you talking to?”

“Something I forgot back at the office. Paperwork.”

She eyed me. “Don’t give me that, Ray. You have your cop face on.”

I have a cop face?

“Are you coming to breakfast?” Jenny asked. She was dressed in white shorts with a striped blue-and-white top. Her dark hair is almost fully gray now, but she dyes it blond. Today the damp strands were pulled back into a high, bouncy ponytail. She tans easily. After a couple of days in the sun, freckles were popping out across her nose. Her long legs and sleek arms were turning a soft brown. We’ve been married for thirty years. We have two adult daughters. I still love Jenny as much as I did on our wedding day. But things haven’t been easy between us lately. I like working for the UN. I like working in developing countries. There, I believe I can make the sort of difference that drew me into policing in the first place. In Canada, my love for the job was being crushed. Mountains of paperwork. A steady stream of the same calls from the same miserable people. I considered retiring, but I wasn’t ready for that. Not yet. Jenny encouraged me to take a job with the UN in South Sudan. She knew I needed the change. She knew I wanted to do something important. Now that I’ve been two years in South Sudan and almost a year in Haiti, she wants me home. I don’t know if I’m ready to come home.

I jumped on top of the rumpled sheets on the king-sized bed. I stretched my arms out. Jenny opened the blinds, and yellow light streamed in. I’d gone all out, money-wise, on this vacation. Oceanfront room with balcony in a five-star hotel. I patted the empty space beside me. I winked at her. “Breakfast can wait.”

“But I can’t,” she said.

“We can call room service,” I said. “Later.”

Her face broke into that familiar grin. I haven’t seen it much lately. She crawled across the bed toward me.

We changed into bathing suits and headed down to the beach after a late breakfast in our room. Jenny slathered herself with sunscreen and pulled a big hat over her face. She stretched out in t

he sun. I hid my lily-white skin under an umbrella and took out my book. I tried to remind myself that I was on vacation. But I couldn’t get the image of Robert Savin’s dead face out of my mind. Was it possible he’d been working undercover? Investigating human smuggling rings out of Haiti? I didn’t know of any such operation. But there was no reason I should.

Drops of water fell on my chest. “Did you remember to book the car for Thursday?” Jenny stood over me. Water dripped from her hair and bathing suit.

“Car?”

“The rental car on North Caicos? We’re taking the ferry over and getting a car, remember?”

“Oh. Sorry.”

She dropped to the sand beside me. “What’s the matter?”

“What makes you think something’s the matter?”

“Thirty years of marriage.” She dug her feet into the sand. Her nails were painted bright red. I love red toenails. “Spill, Ray.”

“How’s the water?” I said instead. I never talk to my wife about work. And right now I didn’t want her to know that my mind was on work.

“Beautiful,” she said.

I struggled to my feet. I grabbed her hand and ran toward the ocean. If Savin had been working undercover, Pierre’s questions would alert his bosses to what had happened.

Not my problem.

FOUR

We went to dinner at Somewhere. It’s a quirky place on the beach not far from our hotel. We walked along the sand, holding hands, carrying our shoes and playing in the surf. When we headed back, it would be after dark, so we’d take a cab. This is a safe country. But no place is entirely safe to walk alone on a deserted, unlit beach at night.

The restaurant’s decorated like a beach shack. Like many places here, it has no permanent walls. We took a table on the upper level to watch the sun setting over the island. Jenny ordered a glass of white wine, and I had a beer. We enjoyed our drinks and then called the waiter over to order dinner. Fish tacos for Jenny. Pulled-pork sandwich for me. I almost rubbed my hands together in anticipation. I love living and working in Haiti, but the food leaves a lot to be desired.

I glanced up at a burst of female laughter. Three young women were climbing the stairs. They were white and well tanned and wore colorful dresses. The one in the lead glanced around the room, looking for a table. She spotted me and came over. “Hi there. I hope you’re okay after what happened this morning.” It was Sandy, the paramedic.

“What happened?” Jenny asked.

Sandy’s smile collapsed. “Gosh, didn’t he tell you? I’m sorry if I spoke out of turn.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I said. The bar was crowded. The two women with Sandy were still searching for a table. “Why don’t you and your friends join us until a table comes free?”

“Okay,” she said. “Thanks.”

We made the introductions. The other women had strong English accents. They were teachers living on the island. Sandy told us she was from Toronto. She’d been working here for a year. “I absolutely love it,” she said. “But don’t get me started on dealing with the government.” Turks and Caicos is not an independent country. It’s still a British colony. That can make governance somewhat confusing at times.

“Sandy and I met on the beach this morning,” I said to Jenny. “Unfortunately, a body was found floating in the water. I waited with it until the police and ambulance arrived.”

“A human body?” Jenny said. “How awful.”

“Happens sometimes,” Sandy said. “Not often, but more often than the hotels like. The ocean’s a dangerous place. Fishermen washed overboard. A foolish tourist swimming alone where he shouldn’t. Refugees trying to get away from the police. If they get in past the reef, then they wash up onto the beach.”

“Gross,” one of the teachers said.

“Sometimes,” Sandy said.

“Tell me about these refugee boats,” I said. “Do you get a lot of them here?”

“It’s a big problem,” Sandy said. “People fleeing Haiti, mostly. Leaky boats out at sea, people jammed together like sardines in a can. In a lot of cases, the scumbags say they’re going to the States. Then they dump the human cargo on our beaches and take off with the money. The authorities pick up a lot of them, but many get away.”

“What happens to these people once they’re here?” Jenny asked.

The waiter brought the young women’s drink orders. We clinked glasses.

“Entire slums have sprung up,” Sandy said. “Around Blue Hills, out by Five Cays. They’re full of Haitians. Some are here legally. Many are not.” She spread her arms out. “This is a prosperous country. It has its problems, for sure, but it’s doing well. Many Haitians can’t speak English. Without English, it can be hard to get a good job. With poverty comes crime. People can’t find jobs, what are they gonna do? Some of the illegals are trafficked once they’re here. Women and kids forced into the sex trade. You got tourists, you got sex workers, right? Older women are placed in houses as maids. Men into the shadier parts of the construction industry.”

“That man,” I said. “The dead…” I was aware of my wife sitting across from me. The two teachers sipping colorful cocktails. “The one we saw this morning. Any ideas about him?”

“Big guy like that,” she said, “good clothes, all his teeth, lots of muscle? At a guess, I’d say he’s a snakehead. Fell out with his buddies, probably. A quick knife in the dark. Empty his pockets. Roll him overboard. No muss, no fuss.”

The table fell silent. It was possible she was right. That Robert Savin had turned bad. Many police in third-world countries do. There’s a lot more money to be made on the other side of the law. I thought again of Robert when I’d seen him last. His graduation. The pride in his face. I didn’t believe it. I wouldn’t believe it. If Savin had been on a refugee boat, it wasn’t as a snakehead. He was no human trafficker.

“Hey, those people are leaving.” One of the teachers grabbed her glass. She leaped to her feet. “Have a nice evening.”

“Nice talking to you, Ray,” Sandy said. She followed her friends to their table.

Jenny looked at me. She was not smiling. “Remember, we’re here on vacation, Ray. It’s a sad story, but please don’t get involved.”

FIVE

With very poor timing, Pierre phoned me when Jenny and I were at breakfast. She threw me a look that threatened to curdle the cream in my coffee. “I thought,” she bit off the words, “you said you were going to turn that thing off.”

“Sorry,” I mumbled. I pushed away from the table and went onto the verandah to talk. A large blue bird I couldn’t identify watched me from the wide leaves of a royal palm. A pretty maid gave me a gentle smile as she passed, pushing a cart piled high with clean yellow-and-white towels. The clear waters of the infinity pool sparkled. The calm sea stretched to the horizon. The sun was rising in a cloudless sky. I guess that’s why they call this place paradise.

“What’d you find out?” I asked.

“Robert Savin took a leave of absence two weeks ago. He said he had urgent family matters to see to. No one has seen or talked to him since. I went around to his house in Jalousie. No one was at home. I spoke to some of the neighbors.”

Jalousie is a brightly painted slum on the hillside overlooking Port-au-Prince. Savin should have been able to afford a better place to live. I wondered if he had other expenses or was just trying to save his pay. At Jalousie, people lived in their neighbors’ pockets. Hard to keep your comings and goings secret in a place like that.

“Robert’s brother is named Jean-Claude. A month or so ago they had a heck of a big fight. Jean-Claude up and left.”

“Was that the same time Robert took this leave?”

“No. The boy left a couple of weeks before, the neighbor said. The brothers fought a lot. Much yelling, sometimes brawling. The neighbors were glad to see the back of Jean-Claude. He wasn’t popular. The woman next door said he played his music at all hours. She was very unhappy, as she has a small baby that has trouble slee

ping.”

“Playing music? You mean records and such?”

“Sometimes. American rap music. Many times when Robert was at work, the boy’s friends would come. They would play instruments, very badly, and Jean-Claude would sing. He had, the woman told me, no talent. She argued with him about the noise. She did not like him. She was very glad when he left.”

“And Robert?”

“She likes Robert. He’s a kind man, she says. She doesn’t know where he has gone. She did not see him leave.”

“Thanks, Pierre. Let me know if you hear anything more. Oh, one more thing. Can you forward a copy of his official picture to my phone?”

“Will do. Are you having a nice vacation?”

I glanced through the open walls into the restaurant. Jenny had her book out and was reading as she nibbled on fresh tropical fruit. She did not look happy. “Peachy keen,” I said.

I put my phone away and went back to the table. I sat down and gave her a smile. “All sorted.” My poached eggs had congealed into a cold, hard lump on top of soggy toast. Fortunately, breakfast was a buffet, so I could toss it and get more. I pushed aside a niggle of guilt at the waste of good food. “What’s the plan for today?”

“I’m going to the spa.”

“Oh, right.” Jenny’s mother had given her the jaw-droppingly expensive spa day as an early birthday present. “Guess I’m on my own then.”

She peered at me over the top of her book. “I guess you are.”

The moment the door closed behind Jenny, I reached for the phone. I called the commissioner of police to introduce myself. I was told he was out of the country. Would I like to speak to the assistant commissioner? “Sure,” I said. But he was in meetings all day. I decided not to wait. As I’d told Pierre, I didn’t have a lot of time.

Silent Night, Deadly Night

Silent Night, Deadly Night Coral Reef Views

Coral Reef Views Deadly Summer Nights

Deadly Summer Nights Murder in a Teacup

Murder in a Teacup Whiteout

Whiteout Dying in a Winter Wonderland

Dying in a Winter Wonderland Tea & Treachery

Tea & Treachery Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen

Rest Ye Murdered Gentlemen Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Body on Baker Street: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery Body on Baker Street

Body on Baker Street Gold Mountain

Gold Mountain Blue Water Hues

Blue Water Hues Hark the Herald Angels Slay

Hark the Herald Angels Slay Murder at Lost Dog Lake

Murder at Lost Dog Lake Blood and Belonging

Blood and Belonging A Winter Kill

A Winter Kill White Sand Blues

White Sand Blues Scare the Light Away

Scare the Light Away Burden of Memory

Burden of Memory More Than Sorrow

More Than Sorrow In the Shadow of the Glacier

In the Shadow of the Glacier Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery

Gold Digger: A Klondike Mystery Gold Web

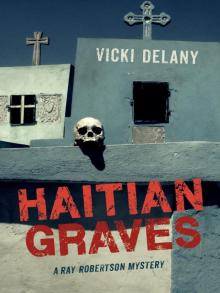

Gold Web Haitian Graves

Haitian Graves Valley of the Lost

Valley of the Lost We Wish You a Murderous Christmas

We Wish You a Murderous Christmas Negative Image

Negative Image A Scandal in Scarlet

A Scandal in Scarlet Juba Good

Juba Good Winter of Secrets

Winter of Secrets Unreasonable Doubt

Unreasonable Doubt Gold Fever

Gold Fever Among the Departed

Among the Departed Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery

Elementary, She Read: A Sherlock Holmes Bookshop Mystery The Cat of the Baskervilles

The Cat of the Baskervilles